Search results for the tag, "Published Writing"

July 5th, 2005

Many of us would say that we believe in a philosophy of live and let live. Most of us, however, probably aren’t awakened at 3 a.m. on consecutive weeknights by johns leaving a brothel in the apartment next door. Most of us probably don’t happen upon the sale of cocaine in our driveway.

Indeed, it’s one thing to support decriminalizing prostitution and drugs from an ivory tower. But now that I’ve graduated college, and am living on my own, I wonder if the ban on these so-called victimless crimes is, in fact, reasonable?

A libertarian would argue that what’s immoral should not necessarily be illegal. Paying for sex and getting high may be self-destructive, but both are voluntary choices.

To put it another way, freedom is not coextensive with virtue; vices should not be crimes. In fact, vice often permeates a free society, which imposes on each individual the responsibility to tolerate objectionable behavior. Moreover, who’s sleeping with whom and who’s using what neither harms me nor infringes my rights.

Critics respond that the everyday consequences of decriminalization outweigh abstract notions of unfettered liberty. For instance, after promising riches to young women, pimps keep them tethered to the netherworld through blackmail, inflating their back pay, and even old-fashioned coercion. With respect to drugs, toking up marijuana is allegedly a gateway to shooting up heroin.

These concerns are real, yet they only tell half the truth. In short, the concerns largely arise not because of the crimes themselves, but because of the laws that criminalize the said acts.

It’s less complicated than it sounds.

For instance, contrast black markets, under which prostitution and illegal drug use occur, with free markets. Owing to the dearth of competition and the risk of being busted or extorted, black markets are more expensive and more dangerous than free markets. While black markets incubate graft and omertas, free markets encourage written contracts and public scrutiny. While justice in the black market comes at the barrel of a gun, justice in the free market comes in a courtroom.

Specifically, under current law, both prostitutes and clients lack any legal recourse—if, say, she passes onto him a sexually transmitted disease or if he physically abuses her. Similarly, try getting a refund from a dealer who sold you schwag instead of something hydroponic. Decriminalization would make fraud legally enforceable and shine some much-needed sunlight into these no-man’s-lands.

Indeed, if we were to treat sex and drugs as we do booze, then many hookers and pushers would go legit or go out of business. Instead of employing backseats and back alleys, they could conduct their affairs in offices—in fear not of the FBI but of the IRS.

Furthermore, under current law, two-thirds of the federal government’s budget for the war on drugs goes to incarceration rather than treatment. Surely, however, nonviolent users would be better served by spending time with physicians and psychiatrists than doing time with rapists and robbers. In fact, studies show that prison does little to fight addiction, whereas rehabilitation helps the individual to break his dependency—and thus check the aforementioned gateway.

The world’s oldest trade and perhaps its most profitable one have always outwitted attempts at suppression; no amount of legislation has, or will, defeat man’s yen for pleasure. We would do better as a people and a polity if we recognized this stubborn fact.

May 1st, 2005

This isn’t a 404 error; the page you’re looking for isn’t missing. I just moved it—in fact, I created a microsite for it.

April 4th, 2005

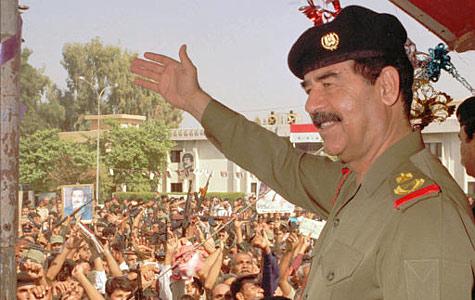

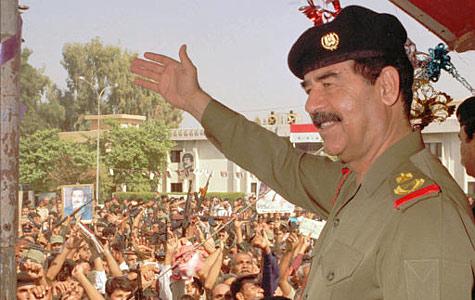

In the 16 months between Sept. 11, 2001, and the Iraq war—despite considerable efforts to entangle Saddam Hussein in the former[1]—hawks came up seriously short. Consequently, neither of the Bush administration’s two most publicized arguments for the war—the President’s State of the Union address and Secretary of State Colin Powell’s presentation to the U.N. Security Council—even mentioned the evidence allegedly implicating Baghdad in our day of infamy. Lest we misconstrue the subtext, on Jan. 31, 2003, Newsweek asked the President specifically about a 9/11 connection to Iraq, to which Bush replied, “I cannot make that claim.”

And yet, seven weeks later, a few days before the war began, the Gallup Organization queried 1,007 American adults on behalf of CNN and USA Today. The pollsters asked, “Do you think Saddam Hussein was personally involved in the Sept. 11th (2001) terrorist attacks (on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon), or not” Fifty-one percent of respondents said yes, 41% said no, and 8% were unsure. What accounts for this discrepancy between the American people and their government

Many blame the media; indeed, it has become a cliché, in the title of a recent book by Michael Massing, to say of antebellum reporting, Now They Tell Us (New York Review of Books, 2004). Such facileness, however, confuses coverage of Iraq’s purported “weapons of mass destructions”—which as some leading newspapers and magazines have since acknowledged was inadequately skeptical[2]—with coverage of Iraqi-al-Qaeda collaboration, which was admirably exhaustive.

Instead, two answers arise. First, the current White House is perhaps the most disciplined in modern history in staying on machine. Although the President denied the sole evidence tying Saddam to 9/11—an alleged meeting in Prague between an Iraqi spy and the ringleader of the airline hijackers in April 2001—the principals of his administration consistently beclouded and garbled the issue. As Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld told Robert Novak in May 2002, “I just don’t know” whether there was a meeting or not. Or as George Tenet told the congressional Joint Inquiry on 9/11 a month later (though not unclassified until Oct. 17, 2002), the C.I.A. is “still working to confirm or deny this allegation.” Or as National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice told Wolf Blitzer in September 2002, a month before Congress would vote to authorize the war, “We continue to look at [the] evidence.” Or as Vice President Richard Cheney told Tim Russert the same day, “I want to be very careful about how I say this. . . . I think a way to put it would be it’s unconfirmed at this point.” Indeed, a year later—even after U.S. forces in Iraq had arrested the Iraqi spy, who denied having met Mohammed Atta—Cheney continued to sow confusion: “[W]e’ve never been able to . . . confirm[] it or discredit[] it,” he asserted. “We just don’t know.”

A second hypothesis is that while Iraq had nothing to do with 9/11, it did have a relationship with al Qaeda. Never mind that at best the relationship was tenuous, that there was nothing beyond some scattered, inevitable feelers. That Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden had been in some sort of contact since the early 1990s allowed the Bush administration to shamelessly conflate their activities pertaining to 9/11 and those outside 9/11.

In this way, as late as October 2004, in his debate with John Edwards during the presidential campaign, Dick Cheney continued to insist that Saddam had an “established relationship” with al Qaeda. Senator Edwards’s reply was dead-on: “Mr. Vice President, you are still not being straight with the American people. There is no connection between the attacks of September 11 and Saddam Hussein. The 9/11 Commission said it. Your own Secretary of State said it. And you’ve gone around the country suggesting that there is some connection. There’s not.”

Two months ago, CBS News and the New York Times found that 30 percent of Americans still believe that Saddam Hussein was “personally involved in the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.” Sixty-one percent disagreed. This is certainly an improvement; yet the public is not entirely to blame. Nor is the Fourth Estate.

Rather, the problem lies primarily with the Bush administration. Andrew Card, George W. Bush’s Chief of Staff, explained it best. “I don’t believe you,” he told Ken Auletta of the New Yorker, “have a check-and-balance function.” In an interview, Auletta elaborated: “[T]hey see the press as just another special interest.” This is the real story of the run-up to the Iraq war: not a press that is cowed or bootlicking, but a government that treats the press with special scorn and sometimes simply circumvents it. As columnist Steve Chapman put it, the administration’s policy was “never to say anything bogus outright when you can effectively communicate it through innuendo, implication and the careful sowing of confusion.”

Indeed, now that we are learning more stories of propaganda from this administration—$100 million to a P.R. firm to produce faux video news releases; White House press credentials to a right-wing male prostitute posing as a reporter; payolas for two columnists and a radio commentator to promote its policies—the big question isn’t about the supposed failings of the press. The question is about the ominously expanding influence of state-sponsored disinformation.

Footnotes

[1] For instance, on 10 separate occasions Donald Rumsfeld asked the C.I.A. to investigate Iraqi links to 9/11. Daniel Eisenberg, “‘We’re Taking Him Out,’” Time, May 13, 2002, p. 38.

Similarly, Dick Cheney’s chief of staff, I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, urged Powell’s speechwriters to include the Prague connection in his U.N. address. Dana Priest and Glenn Kessler, “Iraq, 9/11 Still Linked by Cheney,” Washington Post, September 29, 2003.

[2] See, for instance, The Editors, “Iraq: Were We Wrong,” New Republic, June 28, 2004; [Author unspecified], “The Times and Iraq,” New York Times, May 26, 2004; and Howard Kurtz, “The Post on W.M.D.: An Inside Story,” Washington Post, August 12, 2004.

April 4th, 2005

A version of this blog post was submitted as a nomination for the Hamilton College Christian A. Johnson Professorship.

Last summer, as I struggled to concretize a proposal for a Watson or Bristol postgraduate fellowship, I knew there was one person whose guidance I needed. I had talked with others, but no one had this person’s ability to explain any subject I’d ever asked about with such clarity, conciseness, context and cogence. Add this to patience that never flags and a wit that never runs dry, and this is why I think of Al Kelly as a personal encyclopedia.

I showed up unannounced at his office one weekday, doubtless while he was hard at work on his own research. What made our meeting special is Professor Kelly’s consistent brilliance to immediately distill the essence of an issue. Since my passion for a fellowship far outran any specific ideas for it, we spent about an hour and a half clarifying the reason for and goals of my project. Not where I would travel, or what I would do, or how I would do it, but simply why. Surely, anybody else would have either given up or moved on after say 20 minutes, but here was Professor Kelly calmly, happily connecting disparate dots, drawing out the big picture, and raising points as important as they were seemingly hidden. He knew that without a sound foundation, I was dooming myself to failure.

Yet rather than condescend whatsoever—how, with his intelligence, he does this is extraordinary—Professor Kelly never interrupted but let me hold forth as I attempted to verbalize my thoughts. Only when I finished, as is his unique habit, did he reply, speaking slowly and humbly, choosing his words thoughtfully, and asking me pointed questions. When I left, he transformed my mental chaos into lucidity.

* * *

When I returned to the Hill in the fall, having spent the summer interning at Time magazine, I decided to attend the first faculty meeting as a reporter for the Spectator. As one of maybe three separate students among maybe 150 professors, I entered the Events Barn with uncertainty. Then I spotted Al Kelly, holding court at the back of the room in his usual big chair. I breathed in relief, pulled up a seat and settled in. As the meeting proceeded, he explained some of the finer procedural points, and provided some funny human-interest anecdotes for my article. By next month’s meeting, it was as if I were a colleague.

In October the Spectator asked me to interview President Stewart about the coming presidential election. So I formulated a bunch of questions and then sought out Professor Kelly. I stopped by his office unannounced, and we spent 40 minutes ensuring that each question was relevant, distinct, compact and interesting. Forty minutes on what turned out to be 10 questions? Yes—and without checking his watch once. For unlike interviews I did for my column, this was my first interview to be printed as such, and since I’m an aspiring journalist, Professor Kelly knew it was crucial that I get it right.

Another indelible incident came a few months ago during the Susan Rosenberg affair. As I was weighing the competing arguments for Rosenberg’s appointment, I encountered Professor Kelly leaving the K-J building one night. I asked for his opinion, and in one crisp sentence he made explicit the fundamental principle at stake. I had had countless conversations about the controversy, but, again, Al Kelly was the only one who could simplify everything into a neat, small package.

He would engender another eureka moment for me during the Ward Churchill affair, but perhaps the most important one came during his European Intellectual History course, which I took as a junior. I had raised an objection to something he said, and in five words—“Watch your straw men, Jon”—he significantly altered my approach to scholarship. What this meant, he continued, was that although we all occasionally resort to weak or imaginary arguments, like straw, setup only to be summarily confuted, enlightened discourse proscribes such red herrings.

If this sounds simple, it is. Yet therein lies the beauty of this analysis, which, as is Professor Kelly’s wont, was at once readily comprehensible and crucially insightful. Indeed, his message embodied the goal of a liberal arts education: to further one’s knowledge not by expounding one’s own opinions but by understanding those of others. For this reason, I titled the column I would begin weeks later in the Spec, “No Straw Men.” Similarly, a few months later, I cited Professor Kelly’s exquisite monograph, Writing a Good History Paper, in an op-ed I wrote on journalism. He may be a historian by training, but his wisdom encompasses all disciplines.

* * *

Of course, all the above points to Al Kelly the mentor; doesn’t this guy—the Edgar B. Graves Professor of History after all—teach? Excellently. Al Kelly is of the old school of pedagogy, which means that he sees students not as incubators for his personal politics, but as diverse minds to be filled with classic knowledge. Accordingly, Professor Kelly is an eminently reasonable grader, who I would trust above all others to assess my work fairly. For rather than privilege one’s conclusion, he focuses on the way by which one reaches them. Consequently, his courses are rigorous (to set the tempo, he assigns homework not after but for the first class); challenging (a thorough grasp of the course material is never enough; students must make connections among and outside them); and thorough (you can’t cut any corners for an Al Kelly paper).

Indeed, class with Professor Kelly makes me believe that I’m getting my $35,000 worth of yearly tuition. I come away feeling enlivened and empowered, such that one day, following his Nazi Germany course, he and I continued a discussion from the library all the way to K-J—despite that I was going back to my dorm in North. Even when I didn’t do my homework, I always looked forward to each 75-minute session, because in simply listening to Professor Kelly lecture, I learned as much about that day’s topics as about life. Where else would I hear about the so-called four lies of modernity? (The check’s in the mail. I caught it from the toilet seat. I read Playboy for the articles. And it’s not about the money.)

Finally, rather than ask students just to defend or argue against a view, Professor Kelly requires that we engage it creatively. One typical question, from a final exam, went like this: pretend you’re Mary Wollstonecraft, and write a book review of Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France. Equally impressive is his feedback on our answers, which is why in January I asked him for feedback on my senior thesis in government. He uses few words, but they’re the pithiest I’ve ever received. Were he alive, William Strunk Jr., the initial author of The Elements of Style, would surely take great satisfaction in knowing that others take seriously his maxims to “omit needless words” and to “make every word tell.” The world could use more Al Kellys.

Unpublished Notes

I met Al Kelly in the fall of 2002, when I was a sophomore. We were serving ourselves from a buffet in the Philip Spencer House, following or before a lecture, and I wanted to strike up a conversation. So I asked him what he thought of David Horowitz’s performance in a recent panel with Maurice Isserman. I forget his answer, but when I replied that Horowitz complains he rarely gets invited to speak about the 60s, a subject on which he considers himself an authority, Al’s reply was, as usual, witty and indelible: “That’s because he’s a jerk.”

As a then-fan of Horowitz’s, I didn’t know what to say, and let the issue drop. Yet I couldn’t shake my discomfort, and when I later did a Google search, it was evident Al was right. With just five little words he had changed my mind on something about which I was convinced those with disagreed with me had to be biased.

My next encounter with Al came in my sophomore seminar, Classics of Modern Social Thought, which he teaches with Dan Chambliss. To be honest, I disliked the course, and even argued with the professors about a couple of grades. Neither budged, yet for some reason, as students were choosing our courses for the next semester, I signed up for Al’s European Intellectual History course.

Of course, when I returned to the Hill for my junior year, I had second thoughts about taking another course with Professor Kelly. Hadn’t I suffered through my sophomore seminar? Shouldn’t my grade have been higher? And who cared about European intellectual history anyway? Nonetheless, I decided to attend the first class, which turned out to be one of the best decisions I’ve made while here. Indeed, so much did I enjoy and benefit from learning under Al Kelly that next semester I took his Nazi Germany course, which proved to be my favorite.

* * *

Try as I do to stump him—averaging probably three questions a class—it seems his knowledge knows no bounds. Moreover, his ability to impart that expertise—whenever I ask, however confusedly I render my questions—never ceases to flow forth clearly, concisely, contextually and cogently.

* * *

He made a point to shake the hands of each student after the last class in his Nazi Germany course.

February 11th, 2005

A version of this blog post appeared in the Utica Observer-Dispatch on February 11, 2005, and was noted on Cox & Forkum on March 28, 2005.

HAMILTON COLLEGE, February 1, 2005— On Thursday, February 3, Ward Churchill, a Professor and Chair of Ethnic Studies at the University of Colorado at Boulder, will participate in a panel here titled “The Limits of Dissent.” That he will discuss his infamous essay, “Some People Push Back: On the Justice of Roosting Chickens”—wherein, among other bizarre indictments, he calls the civilians in the World Trade Center on 9/11 “little [Adolf] Eichmanns”—has rightly invited debate.

What troubles many the most is obviously Churchill’s ramblings on 9/11, which are odious, fatuous and sorely lack both credibility and seriousness. Indeed, in an interview in April 2004, he said it was a “no-brainer” that “more 9/11s are necessary.” Last week he declined to back off his Eichmann analogy, which evidently is one of his pet phrases. Then, in a statement on Monday, he assured us that the phrase applies “only to . . . “technicians.’”

With such apoplectic venom for America and Americans, one might think Mr. Churchill would just as fiercely champion the freedom of speech. In fact, for more than a dozen years, he has led organized protests, the last one culminating in arrest, to suppress Columbus Day parades. He reminds his followers that the First Amendment doesn’t protect outrageous forms of hate speech. Apparently, hypocrisy doesn’t bother those who thrive on it.

Yet controversy, especially in academe, is necessary, no idea is dangerous or too radical, and the best disinfectant is sunlight. The bigger issue is that it behooves institutions of higher education, particularly elite ones like Hamilton, to maintain high standards in proffering their scarce and prominent microphones. A commitment to free speech—even an absolute one—does not require a school to solicit jerks, rabble-rousers or buffoons.

This is not to say that the grievance or blowback explanation of 9/11—that it’s not who we are and what we stand for, but what we (U.S. foreign policy) does—doesn’t deserve attention. It does, as Newsweek’s Christopher Dickey argued here last semester. The point is, What suddenly makes Ward Churchill an authority on Islamic terrorism? Ditto for Churchill’s colleague, wife and fellow panelist, Natsu Taylor Saito, whose newfound expertise and lecture subject is the Patriot Act. The answer lies not in “what?” but in “whom?”

That “whom” is the Kirkland Project for the Study of Gender, Society and Culture, a faculty-led organization, well funded primarily by the dean’s office. In recent months, the K.P. has become a lightning rod for Hamilton. Its appointment of Susan Rosenberg, a terrorist turned teacher who four years ago was serving out a 58-year sentence in federal prison, brought to the Hill heretofore the most damaging publicity in its 200-year history. Granted, since controversy inheres in its role as an activist interest group, the K.P. has made waves since its founding in 1996. The evidence, however, increasingly indicates that the group courts controversy—and only one side of controversy—as an end in itself.

To be sure, Churchill was initially scheduled to lecture on Indian rights and prisons, and the change in topic and format occurred at the direction not of the K.P. but of the college president. But surely no one doubts that Churchill was invited largely because he is a leftist radical (it’s worth noting that he lacks a PhD). Similarly, the K.P. excludes topics or speakers who don’t pass that ideological litmus test.

Whether it’s an appropriate for such a group to exist on campus is, fortunately, no longer taboo, since Hamilton’s administration has appointed a faculty committee to review the “mission, programming, budget, and governance” of the Kirkland Project. Formally, the review is a routine procedure about every 10 years, but in this case it’s overdue. Whatever the ensuing recommendations, one hopes that the Board of Trustees and the Kirkland Endowment will also take this opportunity to reevaluate the use of their generosity. The college boasts too much talent to be consumed by another gratuitous scandal.

Addendum (5/7/2005): On September 11, 2002, the following words were written: “The real perpetrators [of the 9/11 attacks] are within the collapsed buildings.” The writer? Saddam Hussein. Would Ward Churchill have disagreed?

Addendum (7/9/2005): Proving that what you say is as important as how you say it, now even Fouad Ajami is on record that U.S. foreign policy—specifically, our “bargain with [Mideast] authoritarianism”—“begot us the terrors of 9/11.”

Of course, there’s no outcry over Ajami since, unlike Churchill, this professor does not need to use phrases like “little Eichmanns” to make his point.

January 27th, 2005

A version of this blog post appeared in FrontPage Magazine on January 27, 2005.

They call academe the ivory tower. But sometimes the ivory tower is not as aloof as it often seems. To the contrary, as the faculty of Hamilton College gathered for their last monthly meeting of 2004, they tackled the agenda with such pragmatism and sincerity one might have mistaken the scene for a town hall meeting.

Except the debate wasn’t about war or taxes or health care. And then there was the philosophy professor who invoked Kant. No, the 800 pound gorilla was Susan L. Rosenberg, Hamilton’s newest faculty member. As an “artist/activist in residence” under the aegis of the Kirkland Project for the Study of Gender, Society and Culture, Ms. Rosenberg was scheduled teach a five-week seminar this winter titled “Resistance Memoirs: Writing, Identity, and Change.”

Sound like a typical teacher? Think again. For only via an act of clemency, among 139 commutations and pardons President Clinton issued two hours before he left office in 2001, was Rosenberg freed from federal prison. Seventeen years earlier, she had been convicted of possessing false identification papers and a stockpile of illicit weapons, including over 600 pounds of explosives—approximately the same poundage Al Qaeda used to bomb the U.S.S. Cole in 2000. To be sure, the feds never charged Rosenberg with murder, but as National Review’s Jay Nordlinger wrote shortly after her commutation, she was a support player—“driver of getaway cars, hauler of weapons, securer of safe houses”—in the Weather Underground, the notorious American terrorist group active in the late 60s and 70s.

Rosenberg has steadfastly denied involvement in the Underground’s most infamous operation, the robbery of a Brink’s money truck in 1981 that left two people seriously wounded and three dead, including two police officers. Moreover, former New York City mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani, who as a U.S. Attorney prosecuted the case, eventually dropped her indictment. Does the presumption of innocence before proven guilty exclude Susan Rosenberg?

Critics contextualize the Brink’s trial, as they do Ms. Rosenberg’s. In the former, the absence (due to memory loss) of a key witness compelled the government to shelve the charges against Ms. Rosenberg without prejudice. In the latter, with the courthouse thick with guards and helicopters whirring overhead, security was costly. Protests and Ms. Rosenberg’s theatrics—she proclaimed herself a “revolutionary guerrilla,” harangued the court about world affairs, demanded, and received, the maximum sentence for her “political” activities—further exacerbated the milieu. The government finally decided to spare taxpayers the expense and time for what would likely be a concurrent verdict.

Furthermore, as Roger Kimball opined in the Wall Street Journal in December, “It is by no means clear that Susan Rosenberg is an ‘an exemplar of rehabilitation,’” as Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz, Professor of Comparative Literature and Director of the Kirkland Project, calls her. Instead, in an interview on Pacifica radio days after her release, Ms. Rosenberg parses her words to renounce individual but not collective violence. “Nobody renounces collective violence,” Professor Rabinowitz assured me. In this way, Ms. Rosenberg’s alleged rehabilitation pertains to means, not ends; she remains an unreconstructed extremist, who even as the Kirkland Project inadvertently admitted in a statement, “maintain[s] her ideals.”

Indeed, Ms. Rosenberg exploits the cachet of her past to advance her present. This is why she terms her course one of “resistance,” implying not change but calcification, and clings to her self-description as a onetime “political prisoner.” “The last time I checked,” however, says Brent Newbury, president of the Rockland Country Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, “we don’t have political prisoners in this country. We have criminals.”

At the same time, Susan Rosenberg is on record in her clemency appeal as accepting responsibility for her actions and for renouncing violence. Both Birch Bayh, a former U.S. senator who chaired the subcommittee on constitutional rights, and the chaplain at Rosenberg’s penitentiary in Danbury, CT, under whose supervision she worked for three years, have vouched for her sincerity. And in any event, don’t actions speak louder than words? Ms. Rosenberg has a master’s degree in writing, has won four awards from PEN Prison Writing programs, and for the past several years has taught literature as an adjunct instructor at CUNY’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice. She also has lectured at such institutions as Columbia, Brown and Yale. Such progress was hard-earned and is hard evidence.

However, some believe that certain acts are so heinous, they disqualify one for full-fledged rehabilitation. Time never exonerates serious criminality. As U.S. Attorney Mary Jo White wrote to the U.S. Parole Commission, “Even if Susan Rosenberg now professes a change of heart . . . the wreckage she has left in her wake is too enormous to overlook.” Economics professor James Bradfield concurs: “[H]er character, as manifestly demonstrated by the choices that she made as an adult over a sustained periods of years, would preclude her appointment to the faculty of Hamilton College.”

President Joan Hinde Stewart disagrees. “No one is irredeemable—I think that is incontrovertible,” she told the faculty. Learning from mistakes “affirms the value of education,” adds Professor Rabinowitz. Most people who have seen The Shawshank Redemption, or listened to a recovering alcoholic speak about his disease, would agree. For while some may not deserve a third or fourth chance, most should get a second. People can and do change, and when we stop believing in that capacity to grow, in the transformative power of the human spirit, we stop believing in the reason to get up in the morning.

But it behooves us to distinguish between morbid curiosity and value. Certainly, Ms. Rosenberg offers a unique perspective, but neither uniqueness nor exclusivity is an end in itself. The end is academic substance. And the means is academic credentials, since even if “Resistance Memoirs” is merely a five-week, half-credit course, that credit nonetheless counts toward a Hamilton College diploma. To be sure, adjuncts need not have a PhD or scholarly publications; yet it is not too much to ask, as several professors did fruitlessly, that Ms. Rosenberg’s curriculum vitae be made available. Plus, just as John Kerry made his service in Vietnam a cornerstone of his recent presidential bid, and consequently suffered criticism for that admittedly heroic record, so the Kirkland Project’s distortion of Ms. Rosenberg’s background invited scrutiny. “[I]ncarcerated for years as a result of her political activities with the Black Liberation Army,” as fliers around the campus announced, sanitizes a vile and vicious rap sheet.

Moreover, surely there was someone with more qualifications, or at least with less baggage? In fact, Professor Rabinowitz told me, “We did not look for anyone else.” In other words: we wanted Susan Rosenberg because she was a convicted, leftwing terrorist.

Rosenberg’s supporters, who include Professors of History, Government and Comparative Literature Maurice Isserman, Stephen Orvis and Peter Rabinowitz (Nancy’s husband), believe the controversy resulted from right-wing polemicists into whose preexisting agendas Susan Rosenberg happened to fall. After all, the Kirkland Project, many of whose almost 40 members are Hamilton professors, approved Ms. Rosenberg’s hire, and Ms. Rosenberg visited Hamilton in February, during which she participated in two panels on “the science of incarceration” and “making change/making art.” Her presence, then or at the aforesaid schools, stirred little attention (though John Jay has since announced that it will not renew her contract.)

All this is true, yet all this discounts the qualitative difference between teaching a credit-bearing course for five weeks and lecturing for two days. Such naïveté further snubs the hundreds of heartfelt pleas to the college, not only from readers of FrontPage Magazine but also from people whom the Weather Underground’s activities intimately, permanently affected. Edward F. Moore, President of the New York state chapter of the F.B.I. National Academy Associates, who wrote an open letter to President Stewart, has no axe to grind, merely a conscience to quiver.

In the end, Susan Rosenberg withdrew herself. Her legacy at Hamilton will not be the pros and cons of her appointment, but the process by which the arguments and their proponents wrestled: passionately but professionally, with moral seriousness and deep principles on both sides. The Board of Trustees wisely refrained from micromanaging this explosive affair, trusting instead in free and open exchange among the faculty. They, like students and alumni, did not disappoint. In fact, our letters and essays in the school newspaper and discussions in class, on ListServs and at meetings, testify to the continuing vitality and vigor of higher education.

October 11th, 2004

Conventional wisdom holds that 9/11 “changed everything.” And so, in the second presidential debate last week, George Bush maintained that “it’s a fundamental misunderstanding to say that the war on terror is only [limited to] Osama bin Laden.” Is it?

Nearly all agree that the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, constituted a watershed, since never before had one day claimed the lives of more American civilians—and on U.S. soil, in our political capital, Washington, DC, and our spiritual capital, New York City—and in peacetime. As such, 9/11 exposed a festering wound, rousing Americans to the acute reality of what could happen if powerful weapons fall into the hands of those with no scruples about using them and no sympathy for those they slaughter.

Hawks argue that this unforeseen crucible gives every reason to assume worst-case scenarios—September 11, 2005, when terrorists let loose anthrax during rush hour at Grand Central Station; September 11, 2010, when terrorists detonate nuclear devices in Times Square, Harvard Square and Capitol Hill—these horrors are no less implausible than September 11, 2001, when terrorists synchronously hijacked four jetliners, full of fuel and innocents, and flew two of them into the World Trade Center and one into the Pentagon. This new era thus rightly shifted the U.S. national security posture from preempting probabilities to preventing possibilities, and counsels casus belli on a lesser standard than imminence. Threats now need only to be “gathering” (Bush’s word) or “emerging” (Kenneth Pollack’s).

Yet rather than exploit our national tragedy to lump all threats together, strategic discrimination should supersede moral clarity. We must distinguish between Al Qaeda, a highly adaptable, decentralized, clandestine network of cells dispersed throughout the world, whose assets are now essentially mobile, and rogue states, which comprise institutions of overt, bordered governments with, as writer Matt Bai puts it, capitals to bomb, ambassadors to recall, and economies to sanction.

Whereas fanatical fundamentalists hate “infidels” more than they love their own lives, secular nationalists love their lives more than they hate us. Whereas suicide bombers are bent on martyrdom as a means to copulate with 72 virgins, Baathists focus on their fortunes here and now. Whereas Osama’s ilk is simply undeterrable, thus justifying the aforesaid shift, Saddam was always eminently deterrable, and failed to warrant such change.

Military historian Victor Davis Hanson remains unconvinced. “While Western elites quibble over exact ties between the various terrorist ganglia, the global viewer turns on the television to see the same suicide bombing, the same infantile threats, the same hatred of the West, the same chants, the same Koranic promises of death to the unbeliever, and the same street demonstrations across the world.” Terrorists and tyrants with (or building) unconventional weapons are different faces of the same diabolical danger.

Alas, such views are all-too familiar, and evoke the alleged communist monolith of the Cold War. As Jeffrey Record observes in a 2003 monograph published by the U.S. Army War College, American policymakers in the 1950s held that a commie anywhere was a commie everywhere, and that all posed an equal threat to the U.S. Such conceptions, however, blinded us to key differences within the “bloc,” like character, aims and vulnerabilities. Ineluctably, the Vietcong—like the Baath today—became little more than an extension of Kremlin—or Qaeda—designs, thus leading Americans needlessly into our cataclysm in Southeast Asia, as in Iraq today.

Unpublished Notes

No

The Baathists are not fundamentalists . . . [T]hey are much more concerned with building opulent palaces on the bodies of those they murder. That’s why Osama Bin Laden thought Hussein to be a[n] infidel.”[9]

“History did not begin on September 11, 2001.”[10]

American responses to 9/11 echoe the fear of the McCarthy era

Surrounded by enemies, most of whom still seek its destruction, Israel has endured 9/11-like carnage regularly since 1948. Insulated by two vast oceans, the United States of America, history’s strongest superpower, can also wither it.

“As evil as Mr. Hussein is, he is not the reason antiaircraft guns ring the capital, civil liberties are being compromised, a Department of Homeland Defense is being created and the Gettysburg Address again seems directly relevant to our lives.”[11]

Yes

“[N]ew threats . . . require new thinking.”[12]

The convention that war is just only as a response to actual aggression is outdated, conceived in an era of states and armies, not suicide bombers.[13]

While deterrence worked against the Soviets because as atheists, they valued this life above all, deterrence is vain against the fanatical fundamentalists of Al Qaeda, who see the here and now as a mere means to heaven.

9/11 shifted U.S. war policy from erring on the side of risk (as the world’s invincible superpower) to erring on the side of caution (as the world’s conspicuously vulnerable superpower).

[9] Chris Matthew Sciabarra, “Saddam, MAD, and More,” SOLOHQ.com, December 18, 2003.

[10] Jim Henley, “The Best We Can Do,” Unqualified Offerings, March 2, 2003.

[11] Madeleine K. Albright, “Where Iraq Fits in the War on Terror,” New York Times, September 13, 2002.

[12] George W. Bush, Speech, United States Military Academy, West Point, New York, June 1, 2002.

[13] Michael Ignatieff, “Lesser Evils,” New York Times Magazine, May 2, 2004.

October 7th, 2004

A version of this blog post appeared in the Hamilton College Spectator in two parts, on October 7, 2004, and October 14.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky once said that we can judge a society’s virtue by its treatment of prisoners.

Likewise, we can judge a society’s freedom by its treatment of minorities. For freedom makes it safe to be unpopular; this is why the First Amendment fundamentally protects dissent. Playing the title character in the movie The American President (1995), Michael Douglas crystallizes the point: “‘You want free speech? Let’s see you acknowledge a man whose words make your blood boil, who’s standing center stage and advocating at the top of his lungs that which you would spend a lifetime opposing at the top of yours.’”

This is of course a Tinseltown vision, familiar more from the mind of Voltaire than in daily life. What if the speaker were calling interracial marriage “a form of bestiality,” a la Matt Hale of the Creativity Movement (formerly the World Church of the Creator)?[1] What if the speaker were waving a placard that says, “God Hates Fags,” a la supporters of Jael Phelps, a candidate for city council in Topeka, Kansas?[2] What if the speaker were suggesting that “more 9/11s are necessary,” a la professor Ward Churchill?[3]

Such notions represent so-called hate speech, which critics seek to criminalize. They argue that speech is a form of social power, by which the historically dominant group, namely, male WASPs, institutionally stigmatizes and harasses the Other. In this way, mere epithets can inflict acute anguish, so that certain words become inherently abusive, intimidating and persecutory. Explains Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, a historian of the Holocaust: We should view such “verbal violence . . . as an assault in its own right, having been intended to produce profound damage—emotional, psychological, and social—to [one’s] dignity and honor.”[4] Adds law professor Charles Lawrence, “The experience of being called ‘nigger,’ ‘spic,’ ‘Jap,’ or ‘kike’ is like receiving a slap in the face.”[5]

Now, that words are never just words, critics are right. With words, a speaker can reach into your very soul, imprinting searing, permanent scars. With words, a speaker can incite individuals to insurrection or vigilantism. Words are weapons. Yet words are always just words, since the breaking of sound waves across one’s ears is qualitatively different from the breaking of a baseball bat across one’s back.[6] Put simply, sticks and stones may break my bones, but words can never truly hurt me.

Specifically, as physical acts, deeds entail consequences over which one has no volition; an engaged fist hurts, whether one wants it to or not. By contrast, one can control one’s reaction to language; to what extent a locution harms one depends ultimately on how one evaluates it.[7] After all, taking responsibility for one’s feelings distinguishes adults from adolescents. Thus, as law professor Zechariah Chafee puts it, banning hate speech “makes a man a criminal . . . because his neighbors have no self-control.”[8] Indeed, with torture chambers in Egypt, genocide in the Sudan and suicide bombing in Israel, equating words with violence is odious. As writer Jonathan Rauch notes, “Every cop or prosecutor chasing words is one fewer chasing criminals.”[9] Plus, if we want to ban speech because it inspires violence, doesn’t history demand that we start with our most beloved book—the Bible—in whose name men have conducted everything from war to inquisition to witch burnings to child abuse?[10]

Still, critics assert that hurling forth scurrilous epithets silences people. The wound is so instantaneous and intense that it disables the recipient. But the law should be neither a psychiatrist nor a babysitter; it should not promote the message, “Peter cast aspersions on Paul. Ergo, Paul is a victim.” That lesson only entails a race to the bottom of victimhood, and implies that one should lend considerable credence to the opinions of bigots. To the contrary, one should recognize that the opinions of bigots are the opinions of bigots.

Consider an incident from the spring of 2004 at Hamilton Collee, wherein one student, face to face with another, called him a “fucking nigger.” Far from cowering, the black students on campus, with the full-throated support of their white peers and faculty, reacted with zeal. Just as the American Civil Liberties Union (A.C.L.U.) predicted 10 years earlier: “[W]hen hate is out in the open, people can see the problem. Then they can organize effectively to counter bad attitudes, possibly change them, and forge solidarity against the forces of intolerance.”[11] Sure enough, with a newly formed committee, a protest, a petition, constant discussion, letters to the editor and articles in the school newspaper, this is exactly what ensued. As if stung, the community sprang into action and bottom-up, self-censorship obviated top-down, administrative censorship.

This is likewise the case outside the ivory tower, since as a practical matter, the more outrageous something is, the more publicity it attracts. Perhaps the most famous example comes from the late 1970s, when neo-Nazis attempted to march through Skokie, Illinois, home to much of Chicago’s Jewish population, many of whom had survived Hitler’s Germany. Although the village board tried to prevent the demonstration, various courts ordered that it be allowed to proceed. Of course, by this time, notoriety and counterprotests caused the Nazis to change venues. Similarly, on September 13, 2001, the Christian fundamentalists Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson accused those who disagreed with their ideology of begetting the terrorist attacks two days earlier. Both have since lost their once-significant political clout.

Better yet, the claim of Holocaust deniers that the Auschwitz gas chambers could not have worked led to closer study, and, in 1993, research detailed their operations. Even the repeatedly qualified, recent musings about gender differences by Harvard president Larry Summers ignited a national conversation about the latest science on the subject. The lesson here is that just as democracy counterbalances factions against factions, so speech rebuts speech. And rather than try to end prejudice and dogma, we can make them socially productive.

For this reason, we should practice extreme tolerance in the face of extreme intolerance. We need not give bigots microphones, but we need to give ourselves a society where, as a 1975 Yale University report describes it, people enjoy the unfettered right to think the unthinkable, mention the unmentionable, and challenge the unchallengeable.[12] Thomas Jefferson got it exactly right upon the founding of the University of Virginia: “This institution will be based on the illimitable freedom of the human mind. For here, we are not afraid to follow truth where it may lead, nor to tolerate error so long as reason is free to combat it.”[13]

Furthermore, with laws built on analogy and precedent, even narrowly tailored restrictions lead to wider ones.[14] Indeed, the transition to tyranny invariably begins with the infringement of a given right’s least attractive practitioners—“our cultural rejects and misfits . . . our communist-agitators, our civil rights activists, our Ku Klux Klanners, our Jehovah’s Witnesses, our Larry Flynts,” as Rodney Smolla writes in Jerry Falwell v. Larry Flint (1988).[15] And since free speech rights are indivisible, the same ban Paul uses to muzzle Peter, Peter can later use to muzzle Paul. Conversely, if we tolerate hate, we can employ the First Amendment for a nobler good, to defend the speech of anti-war protesters, gay-rights activists and others fighting injustice that is graver than being called names. For example, in the 1949 case Terminiello v. Chicago, the A.C.L.U. successfully defended an ex-Catholic priest who had delivered a public address blasting “Communistic Zionistic Jew[s],” among others.[16] That precedent then formed the basis for the organization’s successful defense of civil rights demonstrators in the 1960s and 70s.[17]

And yet critics contend that since hate speech exceeds the pale of reasonable discourse, banning it fails to deprive society of anything important. As much of the Western world has recognized, people can communicate con brio sans calumny. Human history is full enough of hate; shouldn’t we try to make our day and age as hate-free as possible?

Yes, but not as a primary. As writer Andrew Sullivan explains, “In some ways, some expression of prejudice serves a useful social purpose. It lets off steam; it allows natural tensions to express themselves incrementally; it can siphon off conflict through words, rather than actions.”[18] The absence of nonviolent channels to express oneself only intensifies the natural emotion of anger, and when repression inevitably comes undone, it erupts with furious wrath. Moreover, “Verbal purity is not social change,” as one commentator puts it. [19] Speech is a consequence, not a cause of bigotry, and so it can never really change hearts and minds. (In fact, a hate speech law doesn’t even attempt the latter, since it treats as bigots words instead of people.) Rather, a government gun sends the problem underground, and makes bigots change the forms of their discrimination, not their practice of it.

Finally, consider two crimes under a hate speech law. In each, I am beaten brutally, my jaw is smashed and my skull is split in the same way. In the former my assailant calls me a “jerk”; in the latter he calls me a “dirty Jew.” Whereas assailant one receives perhaps five years incarceration, assailant two gets 10. This is unjust for three reasons. First, we usually consider conduct spurred by emotion less abhorrent than that spurred by reason. This is why courts show lenience for crimes of passion, and reserve their greatest condemnation for calculated evil; hence the distinction between first and second-degree murder. A hate speech ban reverses this axiom. Second, such a law makes two crimes out of one, levying an additional penalty for conduct that is already criminal.

Third, the sole reason assailant two does harder time is not because hate motivated him, but because his is hate directed at special groups, like Jews, blacks or gays. Hate crime, then, turns out not to address hate, but politics. For to focus on one’s ideology—regardless of how despicable that ideology is—rather than on the objective violation of a victim’s rights, politicizes the law. Observes writer Robert Tracinski, such legislation “is an attempt to import into America’s legal system a class of crimes formerly reserved only to dictatorships: political crimes.”[20]

In the end, we must make a fundamental decision: Do we want to live in a free society or not? [21] If we do, then we must recognize that the attempt to criminalize hate is not only immoral, it is also impractical. For freedom will always include hate; progress thrives in a crucible of intellectual pluralism; and democracy is not for shrinking violets. As Thomas Paine remarked, “Those who expect to reap the blessings of freedom, must, like men, undergo the fatigues of supporting it.”[22] This, too, is the view of the United States Supreme Court, which in cases like Erznoznik v. Jacksonville (1975) and Cohen v. California (1971) has ruled that however much speech offends one, one bears the burden to avert one’s attention.

What then should we do? If the difference between tolerance and toleration is eradication vs. coexistence, then, as Andrew Sullivan concludes, we would “do better as a culture and as a polity if we concentrated more on achieving the latter rather than the former.”[23]

Footnotes

[1] As quoted in Nicholas D. Kristof, “Hate, American Style,” New York Times, August 30, 2002.

[2] Eric Roston, “In Topeka, Hate Mongering Is a Family Affair,” Time, February 28, 2005, p. 16.

[3] Ward Churchill, Interview with Catherine Clyne, “Dismantling the Politics of Comfort,” Satya, April 2004.

[4] Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust (New York: Knopf, 1996), p. 124.

[5] Charles R. Lawrence III, “If He Hollers Let Him Go: Regulating Racist Speech on Campus,” Duke Law Journal, June 1990.

[6] Stephen Hicks, “Free Speech and Postmodernism,” Navigator (Objectivist Center), October 2002.

[7] Stephen Hicks, “Free Speech and Postmodernism,” Navigator (Objectivist Center), October 2002.

[8] Zechariah Chafee Jr., Free Speech in the United States (Cambridge: Harvard University, 1941), p. 151.

[9] Jonathan Rauch, “In Defense of Prejudice,” Harper’s, May 1995.

[10] Nadine Strossen, Defending Pornography: Free Speech, Sex, and the Fight for Women’s Rights (New York: Scribner, 1995), p. 258.

[11] [Unsigned], “Hate Speech on Campus,” American Civil Liberties Union, December 31, 1994.

[12] “Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression at Yale,” Yale University, January 1975.

[13] “Quotations on the University of Virginia,” Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

[14] Eugene Volokh, “Underfire,” Rocky Mountain News (Denver), February 5, 2005.

[15] Rodney A. Smolla, Jerry Falwell v. Larry Flint: The First Amendment on Trial (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1988), p. 302.

[16] As quoted in Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949).

[17] [Unsigned], “Hate Speech on Campus,” American Civil Liberties Union, December 31, 1994.

[18] Andrew Sullivan, “What’s So Bad About Hate?,” New York Times Magazine, September 26, 1999.

[19] As quoted in [Unsigned], “Hate Speech on Campus,” American Civil Liberties Union, December 31, 1994.

[20] Robert W. Tracinski, “’Hate Crimes’ Law Undermines Protection of Individual Rights,” Capitalism Magazine, November 16, 2003.

[21] Salman Rushdie, “Democracy Is No Polite Tea Party,” Los Angeles Times, February 7, 2003.

[22] Thomas Paine, “The Crisis,” No. 4, September 11, 1777, in Moncure D. Conway (ed.), The Writings of Thomas Paine, Vol. 1 (1894), p. 229.

[23] Andrew Sullivan, “What’s So Bad About Hate?,” New York Times Magazine, September 26, 1999.

Unpublished Notes

Clichés

The vileness of the offense makes it a perfect test of one’s loyalty to the principle of freedom.[1]

Sunlight is the best disinfectant.[2]

Working toward what the free speech scholar Lee Bollinger terms “the tolerant society” by banning intolerance, institutes a do-as-I-say-not-as-I-do, free-speech-for-me-but-not-for-thee standard; our means corrupt our end.

“We are not afraid to entrust the American people with unpleasant facts, foreign ideas, alien philosophies, and competitive values. For a nation that is afraid to let its people judge the truth and falsehood in an open market is a nation that is afraid of its people.”

“I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.”[3]

Speech As Action

“The wounds that people suffer by . . . listen[ing] . . . to such vituperation . . . can be as bad as . . . a . . . beating.”[4]

Granted, such fortitude is idealistic; so is it naïve? Does it trivialize the sincerity or seriousness of one’s pain? Does it intellectualize or universalize something profoundly personal? While the range of responses to hate is vast, the common denominator derives from what Alan Keyes, a former assistant secretary of state, terms “patronizing and paternalistic assumptions. Telling blacks,” for instance, “that whites have the . . . character to shrug off epithets, and they do not. . . . makes perhaps the most insulting, most invidious, most racist statement of all.”[5]

Speech victimizes only if one grants the hater that dispensation.

In the end, one retains the capacity to check, and to exaggerate, the force of input.

As Ayn Rand showed in The Fountainhead, although protagonist Howard Roark endures adversity that would shrivel most men, “It goes only down to a certain point and then it stops. As long as there is that untouched point, it’s not really pain.”

“The only final answer” to hate speech, “is not majority persecution . . . but minority indifference . . . The only permanent rebuke to homophobia is not the enforcement of tolerance, but gay equanimity in the face of prejudice. The only effective answer to sexism is not a morass of legal proscriptions, but the simple fact of female success. In this, as in so many other things, there is no solution to the problem. There is only a transcendence of it. For all our rhetoric, hate will never be destroyed.”[6]

We should not prohibit speech because it leads to violence. The moment one graduates to action—when the harassment turns from verbal to physical taunts—that should be illegal. Then it is no longer a question of taunts, but a question of threats.

Minorities

But don’t minorities deserve special protection? After all, they are invariably the canary in the coalmine of civilization.

At the end of our century, we have once again been faced with an outburst of hatred and destruction based on racial, political and religious differences, which has all but destroyed a country—former Yugoslavia—at least temporarily. Rwanda, Sudan…

But why should an anti-Semite be prosecuted for targeting Jews, while the Unabomber is not subject to special prosecution for his hatred of scientists and business executives? The only answer is that the Unabomber’s ideas are more “politically correct” than the anti-Semite’s.[7]

is, of course, to try minds and punish beliefs.[8]

Hate crime expands the law’s concern from action to thought

But a free-market solution to hate effectively perpetuates the status quo. And though laudable in principle, such a solution lacks force in the face of much of human history, especially the 20th century.

It requires great faith in the power of human reason to believe that people will ultimately become tolerant if left to their devices. Surely, in the absence of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which among other things banned private discrimination, things would not have changed as much anyway.

“require us to believe too simply in the power of democracy and decency and above all rationality; in the ability of a long, slow onslaught” on bigotry.[9]

[1] Ayn Rand, “Censorship: Local and Express,” Ayn Rand Letter, August 13, 1973.

[2] “Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants.” Louis D. Brandeis, Other People’s Money: And How the Bankers Use It (New York: Frederick A Stokes, 1914 [1932]), p. 92.

[3] Evelyn Beatrice Hall, under the pseudonym Stephen G. Tallentyre, The Friends of Voltaire (1906).

[4] Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans the Holocaust (New York: Knopf, 1996), p. 124.

[5] Alan L. Keyes, “Freedom through Moral Education,” Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, Winter 1991.

[6] Andrew Sullivan, “What’s So Bad About Hate?,” New York Times Magazine, September 26, 1999.

[7] Robert W. Tracinski, “’Hate Crimes’ Law Undermines Protection of Individual Rights,” Capitalism Magazine, November 16, 2003.

[8] Jonathan Rauch, “In Defense of Prejudice,” Harper’s, May 1995.

[9] Ursula Owen, “The Speech That Kills,” Index on Censorship, 1998.

September 10th, 2004

No matter how one rationalizes it—duty, the Constitution, necessity, practicality, shared sacrifice—conscription abrogates a man’s right to his life and indentures him to the state. As President Reagan recognized (at least rhetorically), “[T]he most fundamental objection is moral”; conscription “destroys the very values that our society is committed to defending.”[1]

The libertarian argument says that freedom means the absence of the initiation of coercion. Since conscription necessitates coercion, it is incompatible with freedom. Most political scientists, however, believe that freedom imposes certain positive obligations; and so, like taxes, conscription amounts to paying rent for living in a free society.

Which view is right goes to the heart of political philosophy—but the answer is straightforward. If government’s purpose is to protect your individual rights, it cannot then claim title to your most basic right—your very life—in exchange. Such an idea establishes the cardinal axiom of tyranny that hinges every citizen’s existence to the state’s disposal. Nazi Germany, Soviet Russia and Communist China well understood this monopoly. And they demonstrated that if the state has the power to conscript you into the armed forces, then the state has the power to conscript you into whatever folly or wickedness it wants. (This logic is not lost on the Bush administration, which given the dearth of C.I.A. personnel who speak Arabic, has floated plans to draft such specialists.) Moreover, as philosopher Ayn Rand argued, if the state can force you to shoot or kill another human bring and “to risk [your] death or hideous maiming and crippling”—“if your own consent is not required to send [you] into unspeakable martyrdom—then, in principle,” you cease to have any rights, and the government ceases to be your protector.[2]

It matters little that you may neither approve of nor even understand the casus belli, for conscription is the hallmark of a regime whom persuasion cannot bother. This is of course the point, since by inculcating a philosophy of mechanical, unquestioning obedience, conscription churns men from autonomous individuals into sacrificial cogs. What could better unfit people for democratic citizenship?

By contrast, with voluntary armed services, no one enters harm’s way who does not choose that course; the state must convince every potential soldier of the justice and necessity of the cause. To a free society—one rooted in the moral principle that man is an end in himself, that he exists for his own sake—conscription robs men, as the social activist A.J. Muste wrote, “of the freedom to react intelligently . . . of their volition to the concrete situations that arise in a dynamic universe . . . of that which makes them men—their autonomy.”[3]

In this way, conscription exemplifies the “involuntary servitude” the American Constitution forbids. And yet the same Constitution that forbids the state from enforcing “involuntary servitude” (13th Amendment), instructs it to “provide for the common defense” (Preamble) and to “raise and support armies” (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 12). Do these powers not amount to conscription? Not necessarily. David Mayer, a professor of law and history at Capital University, explains: Where the Constitution is ambiguous, we should refer to its animating fundamentals; we should read each provision in the framework “of the document as a whole, and, especially, in light of the purpose of the whole document. . . . [T]hat purpose is to limit the power of government and to safeguard the rights of the individual.”[4] Conscription explicitly contradicts these American axioms.

Even so, some argue that conscription is necessary to ensure America’s survival in the face of, say, a two-front war. A government that acts unconstitutionally in emergencies is better than a government that makes the Constitution into a suicide pact.[5] “Injustice is preferable to total ruin,” the social scientist Garrett Hardin once opined.[6] But stability is neither government’s purpose nor its barometer. True, stability provides the security necessary to exercise one’s freedom; but a government that sacrifices its citizens’ autonomy to prop itself up is no longer a guardian of freedom. To put it another way, the survival of the nation is an imperative, but since the Constitution defines the nation, the nation’s survival is meaningless apart from that relationship. As philosophy professor Irfan Khawaja puts it, “A constitution is to a nation what a brain is to a person: take the brain out, and you kill the person; take large enough chunks of the brain out, and it may as well not be there.”[7]

Yet what if, out of ignorance or indifference, people fail to appreciate a threat before it is too late? Would the 16 million men and women whom the U.S. government conscripted for World War Two—over 12 percent of our population at that time—have arisen, voluntarily, in such numbers, at such a rate, and committed to such specialties as we needed to win the war?[8] Isn’t conscription, as President Clinton termed it, a “hedge against unforeseen threats and a[n] . . . ‘insurance policy’”?[9] Haven’t our commanders in chief—from Lincoln suspending habeas corpus during the Civil War, to FDR interning Japanese-Americans during the Second World War, to Bush’s Patriot Act today—always infringed certain liberties in wartime? In 1919, the Supreme Court declared that merely circulating an inflammatory anti-draft flier, in wartime, constitutes a “clear and present danger.”

Of course, since the price of freedom is eternal vigilance, if one wants to continue to live in freedom, then one should volunteer to defend it when it is threatened. As a practical matter, a dearth of volunteers is often the result of a corrupt war. For instance, without conscription, the U.S. government would have lacked enough soldiers to invade Vietnam; an all-volunteer force (A.V.F.) would have surely triggered a ceasefire years earlier, since people would have simply stopped volunteering. Indeed, rather than deter presidents from prosecuting that increasingly unpopular, drawn-out and bloody tragedy—from sending 60,000 Americans to their senseless deaths—conscription enabled them to escalate it.

Still, even in a just war, enlistments might not meet manpower needs. Sometimes quantity overcomes quality. Napoleon, no neophyte in such matters, noted that “Providence is always on the side of the last reserve.”[10]

But God does not side with the big battalions, but with those who are most steadfast. As President Reagan put it, “No arsenal or no weapon in the arsenals of the world is so formidable as the will and moral courage”[11] of a man who fights of his own accord, for that which he believes is truly just. This is why American farmers defeated British conscripts in 1783, and why Vietnamese guerrillas defeated American conscripts in 1975. Would you prefer to patrol Baghdad today guarded by a career officer, acting on his dream to see live action as a sniper, or guarded by a haberdasher whom the Selective Service Act has coerced into duty and who can think of nothing else save where he’d rather be?

Furthermore, when private firms, in any field, need more workers, they do not resort to hiring at gunpoint. Rather, they appeal to economics, by increasing employees’ compensation. If anyone deserves top government dollar, it is those, who as George Orwell reportedly said, allow us to sleep safely in our beds, those rough men and women who stand ready in the night to visit violence on those who would do us harm.[12]

Nonetheless, isn’t an A.V.F. a poor man’s army, driving a wedge between the upper classes who usually loophole or bribe exemptions, and the middle and lower classes on whose backs wars are traditionally fought? Similarly, doesn’t an A.V.F. devolve disproportionately on minorities, who, as one former Marine captain writes, “enlist[] in the economic equivalent of a Hail Mary pass”?[13] In fact, today’s A.V.F. is the most egalitarian ever. While blacks, for instance, remain overrepresented by six percent, Hispanics, though they comprise about 13 percent of America, comprise 11 percent of those in uniform.[14] Moreover, overrepresentation of a class or race stems not from the upward mobility the armed forces offer—training soldiers in such marketable skills as how to drive a truck, fix a jet or operate sophisticated software—but from the inferior opportunities in society.

Still, critics insist the A.V.F. excludes the children of power and privilege, of our opinion- and policy-makers. Isolated literally and socially from volunteers, these “chicken hawks” can thus advocate “regime change,” “police action,” protecting our “national interests,” or “humanitarian intervention.” After all, as Matt Damon’s character remarks in Good Will Hunting (1997): “It won’t be their kid over there, getting shot. Just like it wasn’t them when their number got called, ‘cuz they were pulling a tour in the National Guard. It’ll be some kid from Southie [a blue-collar district of Boston] over there taking shrapnel in the ass.” “The war,” therefore, as former marine William Broyles Jr. recently noted, “is impersonal for the very people to whom it should be most personal.”[15] By contrast, serving in combat gives one an essential understanding of its horrors, and the more people who serve, the more soberly and honestly will people weigh the real-life consequences of their opinions. It’s exceedingly more trying to beat the warpath if your spouse, friends, children or grandchildren might come home in a body bag (and even more vexing if the government does not censor such coverage).

In theory, this argument has much merit. As a moral issue, however, no matter how egalitarian conscription may be, there is no getting around that it still violates individual rights. Additionally, that veterans, ipso facto, possess better judgment than their civilian counterparts elides that those Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt, neither of whom saw combat, were America’s greatest wartime strategists. Moreover, as journalist Lawrence Kaplan observes, Vietnam left Senators Chuck Hagel (R-NE), John McCain (R-AZ) and John Kerry (D-MA) on three divergent paths, with Hagel a traditional realist, McCain a virtual neoconservative and Kerry a leftist.[16] Experience, while laudable and preparatory, is neither mandatory nor monolithic.

Yet the military integrates blacks and whites, Jews and gentiles, immigrants and nativists, communists and capitalists, atheists and religionists. Esprit de corps breeds national unity. Not for nothing did “bro” enter the American vernacular in the Vietnam era—“Who sheds his blood with me shall be my brother”[17]—nor was it coincidental that the army was the first governmental agency to be desegregated. A speechwriter for President Nixon, who wrote a legislative message proposing the draft’s end, now argues that the “military did more to advance the cause of equality in the United States than any other law, institution or movement.”[18]

Of course, forcing people to wear nametags in public areas would make society friendlier, but no one (except some characters in Seinfeld) entertains this silly violation of autonomy—so why should we entertain it for the most serious violation? Noble and imperative as the ends may be, a civilian-controlled military is not a tool to implement social change, but a deadly machine for self-defense. Further, to advance equality at home one may well need to watch one’s bros die abroad.

But conscription will restore the ruggedness today’s young Americans sorely lack, critics contend. Complacency cocoons my generation, who depend on anything but ourselves. Maybe they even quote Rousseau: “As the conveniences of life increase . . . true courage flags, [and] military virtues disappear.”[19]

Yet soft as we may appear vegging out before M.T.V., history shows that when attacked, Americans are invincible. As President Bush said of 9/11: “Terrorist attacks can shake the foundations of our biggest buildings, but they cannot touch the foundation of America. These acts shattered steel, but they cannot dent the steel of American resolve.”[20] Moreover, the problem is not a dearth of regimentation, but a dearth of persuasion; the administration has failed to convince potential soldiers to enlist. Rather than see this as a sign of pusillanimity, it seems that those with the most to lose think Washington is acting for less than honorable reasons—which should cause the government not to reinstate conscription but to rethink its policies.

In his augural address, JFK acclaimed the morality behind conscription. “Ask not what your country can do for you,” he declared. “Ask what you can do for your country.” But our founders offered us an alternative between parasitism and cannon fodder, between betraying one’s beliefs by serving or becoming a criminal or expatriate by dodging: autonomous individuals pursuing their own happiness, sacrificing neither others to themselves nor themselves to others. The catch-22 goes further, since the prime draftee age, from 18 to 25, in Ayn Rand’s words, constitutes “the crucial formative years of a man’s life. This is . . . when he confirms his impressions of the world . . . when he acquires conscious convictions, defines his moral values, chooses his goals, and plans his future.” In other words, when man is most vulnerable, draft advocates want to force him into terror—“the terror of knowing that he can plan nothing and count on nothing, that any road he takes can be blocked at any moment by an unpredictable power, that, barring his vision of the future, there stands the gray shape of the barracks, and, perhaps, beyond it, death for some unknown reason in some alien jungle.”[21] Death in some alien jungle yesterday—death in some alien desert today.

Footnotes

[1] Ronald Reagan, Letter to Mark O. Hatfield, May 5, 1980. As quoted in Doug Bandow, “Draft Registration: It’s Time to Repeal Carter’s Final Legacy,” Cato Institute, May 7, 1987.

[2] Ayn Rand, “The Wreckage of the Consensus,” in Ayn Rand, Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal. Italics added.

[3] A.J. Muste, “Conscription and Conscience,” in Martin Anderson (ed), with Barbara Honegger, The Military Draft: Selected Readings on Conscription (Stanford: Hoover, 1982), p. 570.

[4] David Mayer, “Interpreting the Constitution Contextually,” Navigator (Objectivist Center), October 2003.

[5] The term “suicide pact” comes from Supreme Court Associate Justice Robert Jackson, who, in his dissenting opinion in Terminiello v. Chicago (1949), wrote: “There is danger that, if the court does not temper its doctrinaire logic with a little practical wisdom, it will convert the constitutional Bill of Rights into a suicide pact.”

See also David Corn, “The ‘Suicide Pact’ Mystery,” Slate, January 4, 2002.

[6] Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science, December 13, 1968.

[7] Irfan Khawaja, “Japanese Internment: Why Daniel Pipes Is Wrong,” History News Network, January 10, 2005.

[8] Harry Roberts, Comments on Arthur Silber, “With Friends Like These, Continued—and Arguing with David Horowitz,” LightofReason.com, November 19, 2002.

[9] William Jefferson Clinton, Letter to the Senate, May 18, 1994.

[10] Burton Stevenson, The Home Book of Quotations (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1952), p. 2114.

[11] Ronald Reagan, First Inaugural Address, January 20, 1981.

[12] For years people have quoted these eloquent words—either “People sleep peaceably in their beds at night only because rough men stand ready to do violence on their behalf,” or, “We sleep safely at night because rough men stand ready to visit violence on those who would harm us”—and attributed them to George Orwell, which was the pseudonym of Eric Blair. Yet neither the standard quotation books, general and military, extensive Google searches, the Stumpers ListServ, nor the only Orwell quotation booklet, The Sayings of George Orwell (London: Duckworth, 1994), cites a specific source.

[13] Nathaniel Fick, “Don’t Dumb Down the Military,” New York Times, July 20, 2004, p. A19.

[14] Nathaniel Fick, “Don’t Dumb Down the Military,” New York Times, July 20, 2004, p. A19.

[15] William Broyles Jr., “A War for Us, Fought by Them,” New York Times, May 4, 2004.

[16] Lawrence F. Kaplan, “Apocalypse Kerry,” New Republic Online, July 30, 2004.

[17] Noel Koch, “Why We Need the Draft Back,” Washington Post, July 1, 2004, p. A23.

[18] Noel Koch, “Why We Need the Draft Back,” Washington Post, July 1, 2004, p. A23.

[19] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “A Discourse on the Moral Effects of the Arts and Sciences,” in Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract and Discourses (London: Everyman, 1993), p. 20.

[20] George W. Bush, Statement by the President in His Address to the Nation, White House, September 11, 2001.

[21] Ayn Rand, “The Wreckage of the Consensus,” in Ayn Rand, Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal.

Unpublished Notes

1. Bill Steigerwald, “Refusing to Submit to the State,” Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, September 19, 2004.

We [draft dodgers] exploited nearly 30 deferments, which—until the draft lottery was instituted in 1969 to make involuntary servitude an equal opportunity for every 18- to 26-year-old—were embarrassingly rigged in favor of the white and privileged and against minorities and working classes.

We went to college (2-S)—for as long as possible. We got married—and had kids ASAP (3-A). We faked diseases and psychoses, made ourselves too fat or over-did drugs (4-F).

We became preachers (4-D) and teachers and conscientious objectors (1-O). We fled to Canada or even committed suicide.

2. David M. Kennedy, “The Best Army We Can Buy,” New York Times, July 25, 2005.

But the modern military’s disjunction from American society is even more disturbing. Since the time of the ancient Greeks through the American Revolutionary War and well into the 20th century, the obligation to bear arms and the privileges of citizenship have been intimately linked.

When our deferments were refused or elapsed, we became draft bait (1-A). . . .

[I]t’s the military draft that’s morally wrong, not the [politician] . . . who dodges it.

3. Christopher Preble, “You and What Army?,” American Spectator, June 14, 2005.

A draft would succeed in getting bodies into uniforms, but conscription is morally reprehensible, strategically unsound, and politically unthinkable. The generals and colonels, but especially the junior officers and senior enlisted personnel who lead our armed forces, know that the military is uniquely capable because it is comprised of individuals who serve of their own free will.

4. Richard A. Posner, “Security vs. Civil Liberties,” Atlantic Monthly, December 2001.

Lincoln’s unconstitutional acts during the Civil War show that even legality must sometimes be sacrificed for other values. We are a nation under law, but first we are a nation. . . . The law is not absolute, and the slogan “Fiat justitia, ruat caelum” (Let justice be done, though the heavens fall) is dangerous nonsense. The law is a human creation . . . It is an instrument for promoting social welfare, and as the conditions essential to that welfare change, so must it change.

5. John Stuart Mill, On Liberty. As quoted in Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars.

The only test . . . of a people’s having become fit for popular institutions is that they, or a sufficient portion of them to prevail in the contest, are willing to brave labor and danger for their liberation.

6. Mario Cuomo. As quoted in William Safire, “Cuomo on Iraq,” New York Times, November 26, 1990.

You can’t ask soldiers to fling their bodies in front of tanks and say, ‘We’ll take our chances on reinforcements.’

the latter means that your right to your own life is provisional—which means you don’t have that right. Instead, you must buy your rights by surrendering your life.

integrate idea of “shared sacrifice” to “poor man’s army” counterargument

Data on Draftees

According to Pentagon officials, draftees tend to serve shorter terms than volunteers, so the armed services get less use out of their training. Draftee military units also don’t jell as well into cohesive fighting forces (Mark Thompson, “Taking a Pass,” Time, September 1, 2003, p. 43).

the lack of unit cohesiveness from constant rotation

“With soldiers now serving 50% longer than they did in the Vietnam era, the Pentagon invests heavily in career-length education and training, helping the troops master the complicated technology that makes the U.S. military the envy of the world” (Mark Thompson, “Taking a Pass,” Time, September 1, 2003, p. 43).

7. Fred Kaplan, “The False Promises of a Draft,” Slate, June 23, 2004.