Search results for the tag, "9/11"

August 23rd, 2007

“Jihadism is a mosquito bite compared to communism.” So says Lieutenant General William Odom, the director of the National Security Agency under Ronald Reagan from 1985 to 1988, in next week’s issue of Time.

It’s a provocative assertion, and Odom, who now works at the neoconservative Hudson Institute, is no dove. But is he right?

On one hand, whereas we could contain Stalin through the policy of mutually assured destruction, suicide bombers are, by definition, undeterrable. Indeed, despite a massive nuclear arsenal, the Soviets never once attacked the United States, whereas al Qaeda succeeded in inflicting the worst assault on American soil ever.

On the other hand, the Soviets were better armed, wealthier and more numerous than al Qaeda. As the New Republic’s Peter Beinhart has put it, “The U.S.S.R. was a totalitarian superpower; al Qaeda merely espouses a totalitarian ideology, which has had mercifully little access to the instruments of state power.” Does anyone doubt that if Osama bin Laden ever acquires a nuke, he would not use it?

Furthermore, the Soviets funded and armed the Koreans and Vietnamese, among other insurgencies. And if you want to compare Communism to al Qaeda-ism, it’s not even close: Communism oppressed billions—virtually all Asia, Latin America, parts of Africa and South America—whereas jihadism has under its boot, at most, tens of thousands.

So is Odom right? The short answer is yes: nuclear weapons, in the hands of a global empire, trump jumbo jets in the hands of 19 men. The long answer, to paraphrase historian Richard Pipes, is that the threat of jihadism is both less menacing than communism, in that jihadis are militarily weaker, and more dangerous, in that they are fanatics who are impervious to negotiation.

* Thanks to Chris Matthew Sciabarra, who helped me answer this very question in college.

Addendum (9/1/2012): Charles Krauthammer articulates the counterargument:

“Deterring Iran is fundamentally different from deterring the Soviet Union. You could rely on the latter but not on the former. . . .

“The mullahs have thought the unthinkable to a different conclusion. They know about the Israeli arsenal. They also know, as Rafsanjani said, that in any exchange Israel would be destroyed instantly and forever, whereas the ummah—the Muslim world of 1.8 billion people whose redemption is the ultimate purpose of the Iranian revolution—would survive damaged but almost entirely intact. . . .

“The mullahs have a radically different worldview, a radically different grievance and a radically different calculation of the consequences of nuclear war.

July 18th, 2005

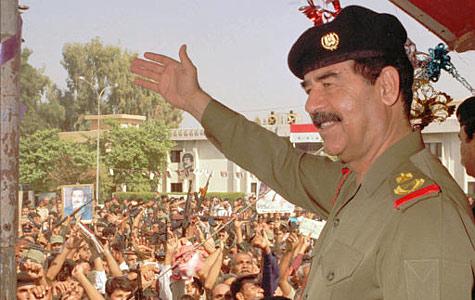

Last month Rep. Robin Hayes, vicechair of the House subcommittee on terrorism, declared that Saddam Hussein was “very much involved in 9/11.” Hayes claimed that he has access to evidence few others do. Told no investigation has ever implicated Baghdad in the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the congressman responded, “I’m sorry, but you must have looked in the wrong places.”

Let’s take another look. Shortly after 9/11, a U.S. official leaked to the Associated Press that “the United States has received information from a foreign intelligence service that Mohamed Atta,” the ringleader of the 9/11 gang, “met earlier this year in Europe with an Iraqi intelligence agent.” As the story unfolded over the next month, the world learned that in early April 2001, Atta had allegedly rendezvoused with Ahmed Khalil Ibrahim Samir al-Ani, a vice consul in Iraq’s embassy in Prague but actually a spymaster. The meeting would have been Atta’s second time in the Czech capital in less than a year, having passed through the city’s airport en route from Germany to New Jersey in June 2000, and was the sole evidence tying Saddam to 9/11.

On one hand, the Czech domestic intelligence service, who by virtue of proximity had the best data, held that the rendezvous happened. It was certainly plausible, since before communist Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 1993, Iraq had been a major buyer of Czechoslovak arms. Additionally, according to Richard Perle, then the chair of the Defense Policy Board, an influential advisory group to the Pentagon, operations like 9/11 “are not planned in caves; they’re planned in offices by people who have secretaries and support staffs and research and communications and technology.” Finally, as James Woolsey, who visited England to investigate the case on behalf of the Justice Department, contends, even with all the ambiguity, the evidence was “about as clear as these things get.”

On the other hand, counters Daniel Benjamin, the director for counterterrorism at the National Security Council from 1998-1999, it is “very difficult to hide serious ties” between a regime and a terrorist client. For in collaborating, “they negotiate over targets, finances, materiel, and tactics.” Similarly, the apparatuses of bureaucracy—including employees who will swap secrets for cash—afford ample opportunity for spying on governments. This is why state sponsors, like Libya vis-à-vis the 1998 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, and Iran vis-à-vis the 1996 attack on the Khobar Towers, have historically left ample trails.

And yet the only Iraqi trail pertaining to 9/11 was one meeting in Prague, during a month for which neither the F.B.I. nor C.I.A. could uncover any visa, airline or financial records showing that Mohamed Atta had left or reentered the U.S. (Their research placed him in Florida two days before the meeting.) Second, all the evidence rested on the uncorroborated allegation of a single informant, who could produce neither any audio nor visual recordings. Third, no one could verify what Atta and Ani had discussed—for instance, whether Atta requested help or updated Ani on his progress. Accordingly, as Cheney told Tim Russert in September 2003. “[W]e’ve never been able to . . . confirm[] [the meeting] or discredit[] it. We just don’t know.”

Of course, circumstantiality is not a basis—or even a partial basis, really—for taking a country to war. After all, the burden of proof always falls on he who asserts a positive. In the 16 months between 9/11 and the Iraq war, despite considerable efforts, hawks failed to meet this burden. Consequently, neither of the administration’s two most publicized arguments for the war—the State of the Union address (1/28/03) and Secretary of State Colin Powell’s presentation to the U.N. Security Council (2/5/03)—even mentioned Prague. And lest we misconstrue the subtext, on January 31—seven weeks before the war began—Newsweek asked the President specifically about a 9/11 connection to Iraq, to which Bush replied, “I cannot make that claim.” Eight months later, in September 2003, Bush repeated, “We’ve had no evidence that Saddam Hussein was involved with September the 11th.”

Moreover, in July 2003, U.S. troops arrested Ani in Iraq. The Iraqi denied ever meeting Atta, a denial that officials found credible. Also in July, the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence and the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence declassified the much-delayed report of their Joint Inquiry into 9/11. Tellingly, nowhere in 858 pages does the report mention Iraq’s purported involvement in our day of infamy. Finally, a year later, the 9/11 Commission Report concluded that “[t]he available evidence does not support the original Czech report of an Atta-Ani meeting.” The report added that Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and Ramzi Binalshibh both denied that any Atta-Ani meeting occurred.

Still, Rep. Hayes persists. The “evidence is clear,” he told CNN. In fact, it is illusory. And at a time when the American people increasingly mistrust journalists for their reliance on anonymous sources, isn’t it time we turn the same scrutiny to politicians who rely on anonymous evidence?

Unpublished Notes

In a 10,500-word article in a recent issue of the Weekly Standard, Stephen Hayes and Thomas Joscelyn charge those who dismiss the Iraq-al Qaeda relationship as having “an acute case of denial”: “We know from these IIS documents that beginning in 1992 the former Iraqi regime regarded bin Laden as an Iraqi Intelligence asset. We know from IIS documents that the former Iraqi regime provided safe haven and financial support to an Iraqi who has admitted to mixing the chemicals for the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center. We know from IIS documents that Saddam Hussein agreed to Osama bin Laden’s request to broadcast anti-Saudi propaganda on Iraqi state-run television. We know from IIS documents that a “trusted confidante” of bin Laden stayed for more than two weeks at a posh Baghdad hotel as the guest of the Iraqi Intelligence Service.”

But ex post facto evidence cannot be a casus belli.

“[T]he Free World is not interested in epistemological debates over what constitutes a connection. We are not engaged in a court case, or a classroom debate. We are fighting a war.” [1]

[1] Claudia Rosett, “Saddam and al Qaeda,” Wall Street Journal, July 13, 2005.

May 1st, 2005

This isn’t a 404 error; the page you’re looking for isn’t missing. I just moved it—in fact, I created a microsite for it.

April 4th, 2005

In the 16 months between Sept. 11, 2001, and the Iraq war—despite considerable efforts to entangle Saddam Hussein in the former[1]—hawks came up seriously short. Consequently, neither of the Bush administration’s two most publicized arguments for the war—the President’s State of the Union address and Secretary of State Colin Powell’s presentation to the U.N. Security Council—even mentioned the evidence allegedly implicating Baghdad in our day of infamy. Lest we misconstrue the subtext, on Jan. 31, 2003, Newsweek asked the President specifically about a 9/11 connection to Iraq, to which Bush replied, “I cannot make that claim.”

And yet, seven weeks later, a few days before the war began, the Gallup Organization queried 1,007 American adults on behalf of CNN and USA Today. The pollsters asked, “Do you think Saddam Hussein was personally involved in the Sept. 11th (2001) terrorist attacks (on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon), or not” Fifty-one percent of respondents said yes, 41% said no, and 8% were unsure. What accounts for this discrepancy between the American people and their government

Many blame the media; indeed, it has become a cliché, in the title of a recent book by Michael Massing, to say of antebellum reporting, Now They Tell Us (New York Review of Books, 2004). Such facileness, however, confuses coverage of Iraq’s purported “weapons of mass destructions”—which as some leading newspapers and magazines have since acknowledged was inadequately skeptical[2]—with coverage of Iraqi-al-Qaeda collaboration, which was admirably exhaustive.

Instead, two answers arise. First, the current White House is perhaps the most disciplined in modern history in staying on machine. Although the President denied the sole evidence tying Saddam to 9/11—an alleged meeting in Prague between an Iraqi spy and the ringleader of the airline hijackers in April 2001—the principals of his administration consistently beclouded and garbled the issue. As Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld told Robert Novak in May 2002, “I just don’t know” whether there was a meeting or not. Or as George Tenet told the congressional Joint Inquiry on 9/11 a month later (though not unclassified until Oct. 17, 2002), the C.I.A. is “still working to confirm or deny this allegation.” Or as National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice told Wolf Blitzer in September 2002, a month before Congress would vote to authorize the war, “We continue to look at [the] evidence.” Or as Vice President Richard Cheney told Tim Russert the same day, “I want to be very careful about how I say this. . . . I think a way to put it would be it’s unconfirmed at this point.” Indeed, a year later—even after U.S. forces in Iraq had arrested the Iraqi spy, who denied having met Mohammed Atta—Cheney continued to sow confusion: “[W]e’ve never been able to . . . confirm[] it or discredit[] it,” he asserted. “We just don’t know.”

A second hypothesis is that while Iraq had nothing to do with 9/11, it did have a relationship with al Qaeda. Never mind that at best the relationship was tenuous, that there was nothing beyond some scattered, inevitable feelers. That Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden had been in some sort of contact since the early 1990s allowed the Bush administration to shamelessly conflate their activities pertaining to 9/11 and those outside 9/11.

In this way, as late as October 2004, in his debate with John Edwards during the presidential campaign, Dick Cheney continued to insist that Saddam had an “established relationship” with al Qaeda. Senator Edwards’s reply was dead-on: “Mr. Vice President, you are still not being straight with the American people. There is no connection between the attacks of September 11 and Saddam Hussein. The 9/11 Commission said it. Your own Secretary of State said it. And you’ve gone around the country suggesting that there is some connection. There’s not.”

Two months ago, CBS News and the New York Times found that 30 percent of Americans still believe that Saddam Hussein was “personally involved in the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.” Sixty-one percent disagreed. This is certainly an improvement; yet the public is not entirely to blame. Nor is the Fourth Estate.

Rather, the problem lies primarily with the Bush administration. Andrew Card, George W. Bush’s Chief of Staff, explained it best. “I don’t believe you,” he told Ken Auletta of the New Yorker, “have a check-and-balance function.” In an interview, Auletta elaborated: “[T]hey see the press as just another special interest.” This is the real story of the run-up to the Iraq war: not a press that is cowed or bootlicking, but a government that treats the press with special scorn and sometimes simply circumvents it. As columnist Steve Chapman put it, the administration’s policy was “never to say anything bogus outright when you can effectively communicate it through innuendo, implication and the careful sowing of confusion.”

Indeed, now that we are learning more stories of propaganda from this administration—$100 million to a P.R. firm to produce faux video news releases; White House press credentials to a right-wing male prostitute posing as a reporter; payolas for two columnists and a radio commentator to promote its policies—the big question isn’t about the supposed failings of the press. The question is about the ominously expanding influence of state-sponsored disinformation.

Footnotes

[1] For instance, on 10 separate occasions Donald Rumsfeld asked the C.I.A. to investigate Iraqi links to 9/11. Daniel Eisenberg, “‘We’re Taking Him Out,’” Time, May 13, 2002, p. 38.

Similarly, Dick Cheney’s chief of staff, I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, urged Powell’s speechwriters to include the Prague connection in his U.N. address. Dana Priest and Glenn Kessler, “Iraq, 9/11 Still Linked by Cheney,” Washington Post, September 29, 2003.

[2] See, for instance, The Editors, “Iraq: Were We Wrong,” New Republic, June 28, 2004; [Author unspecified], “The Times and Iraq,” New York Times, May 26, 2004; and Howard Kurtz, “The Post on W.M.D.: An Inside Story,” Washington Post, August 12, 2004.

October 11th, 2004

Conventional wisdom holds that 9/11 “changed everything.” And so, in the second presidential debate last week, George Bush maintained that “it’s a fundamental misunderstanding to say that the war on terror is only [limited to] Osama bin Laden.” Is it?

Nearly all agree that the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, constituted a watershed, since never before had one day claimed the lives of more American civilians—and on U.S. soil, in our political capital, Washington, DC, and our spiritual capital, New York City—and in peacetime. As such, 9/11 exposed a festering wound, rousing Americans to the acute reality of what could happen if powerful weapons fall into the hands of those with no scruples about using them and no sympathy for those they slaughter.

Hawks argue that this unforeseen crucible gives every reason to assume worst-case scenarios—September 11, 2005, when terrorists let loose anthrax during rush hour at Grand Central Station; September 11, 2010, when terrorists detonate nuclear devices in Times Square, Harvard Square and Capitol Hill—these horrors are no less implausible than September 11, 2001, when terrorists synchronously hijacked four jetliners, full of fuel and innocents, and flew two of them into the World Trade Center and one into the Pentagon. This new era thus rightly shifted the U.S. national security posture from preempting probabilities to preventing possibilities, and counsels casus belli on a lesser standard than imminence. Threats now need only to be “gathering” (Bush’s word) or “emerging” (Kenneth Pollack’s).

Yet rather than exploit our national tragedy to lump all threats together, strategic discrimination should supersede moral clarity. We must distinguish between Al Qaeda, a highly adaptable, decentralized, clandestine network of cells dispersed throughout the world, whose assets are now essentially mobile, and rogue states, which comprise institutions of overt, bordered governments with, as writer Matt Bai puts it, capitals to bomb, ambassadors to recall, and economies to sanction.

Whereas fanatical fundamentalists hate “infidels” more than they love their own lives, secular nationalists love their lives more than they hate us. Whereas suicide bombers are bent on martyrdom as a means to copulate with 72 virgins, Baathists focus on their fortunes here and now. Whereas Osama’s ilk is simply undeterrable, thus justifying the aforesaid shift, Saddam was always eminently deterrable, and failed to warrant such change.

Military historian Victor Davis Hanson remains unconvinced. “While Western elites quibble over exact ties between the various terrorist ganglia, the global viewer turns on the television to see the same suicide bombing, the same infantile threats, the same hatred of the West, the same chants, the same Koranic promises of death to the unbeliever, and the same street demonstrations across the world.” Terrorists and tyrants with (or building) unconventional weapons are different faces of the same diabolical danger.

Alas, such views are all-too familiar, and evoke the alleged communist monolith of the Cold War. As Jeffrey Record observes in a 2003 monograph published by the U.S. Army War College, American policymakers in the 1950s held that a commie anywhere was a commie everywhere, and that all posed an equal threat to the U.S. Such conceptions, however, blinded us to key differences within the “bloc,” like character, aims and vulnerabilities. Ineluctably, the Vietcong—like the Baath today—became little more than an extension of Kremlin—or Qaeda—designs, thus leading Americans needlessly into our cataclysm in Southeast Asia, as in Iraq today.

Unpublished Notes

No

The Baathists are not fundamentalists . . . [T]hey are much more concerned with building opulent palaces on the bodies of those they murder. That’s why Osama Bin Laden thought Hussein to be a[n] infidel.”[9]

“History did not begin on September 11, 2001.”[10]

American responses to 9/11 echoe the fear of the McCarthy era

Surrounded by enemies, most of whom still seek its destruction, Israel has endured 9/11-like carnage regularly since 1948. Insulated by two vast oceans, the United States of America, history’s strongest superpower, can also wither it.

“As evil as Mr. Hussein is, he is not the reason antiaircraft guns ring the capital, civil liberties are being compromised, a Department of Homeland Defense is being created and the Gettysburg Address again seems directly relevant to our lives.”[11]

Yes

“[N]ew threats . . . require new thinking.”[12]

The convention that war is just only as a response to actual aggression is outdated, conceived in an era of states and armies, not suicide bombers.[13]

While deterrence worked against the Soviets because as atheists, they valued this life above all, deterrence is vain against the fanatical fundamentalists of Al Qaeda, who see the here and now as a mere means to heaven.

9/11 shifted U.S. war policy from erring on the side of risk (as the world’s invincible superpower) to erring on the side of caution (as the world’s conspicuously vulnerable superpower).

[9] Chris Matthew Sciabarra, “Saddam, MAD, and More,” SOLOHQ.com, December 18, 2003.

[10] Jim Henley, “The Best We Can Do,” Unqualified Offerings, March 2, 2003.

[11] Madeleine K. Albright, “Where Iraq Fits in the War on Terror,” New York Times, September 13, 2002.

[12] George W. Bush, Speech, United States Military Academy, West Point, New York, June 1, 2002.

[13] Michael Ignatieff, “Lesser Evils,” New York Times Magazine, May 2, 2004.

Scholars “use an intellectual scalpel…