July 14th, 2005

Cooper and Miller, supported by the New York Times (and probably Time magazine, as opposed to Time Inc.), argue that the subpoena requiring them to reveal their confidential sources is unjust. Therefore, in the spirit of civil disobedience, they chose to defy the law and to suffer incarceration.

Of course, the full extension of this reasoning, as Michael Kinsley explains, means that “almost any law anyone does not care for is up for grabs”: “In societies that are not democracies or lack a legitimate judicial system, nonviolent civil disobedience is an admirably restrained method of attempting political change. In societies where laws are democratically enacted and fairly enforced, for the most part, purposely breaking them needs to be justified by some enormous injustice.”

Kinsley is right that civil disobedience should derive from an “enormous injustice.” Yet there are myriad laws with which we each disagree, and to say that only some merit defiance is not for Kinsley to decree, but for each individual to decide by his own lights—so long as he is willing to face the consequences.

Indeed, what counts as an “enormous injustice”? Surely we can agree that conscription and war qualify. But what about sodomy laws? Eminent domain? Denial of service at a private restaurant because you’re black?

Instead of trying to answer these questions collectively, why not use a straightforward criterion: if one deeply believes that a particular law is deeply immoral, then one should nonviolently fight against it. After all, we should follow the law less because it’s the law than because we believe it’s right.

Does this lead to anarchy? I don’t think so, because if a society is strong enough, is just enough, it will withstand trivial acts of disobedience and rectify those that need rectifying.

Therefore, in her refusal to compromise her principles, I stand with Judy Miller.

July 14th, 2005

“By its very nature, government politicizes everything it touches. Science is no exception. Stem cell research needs neither government money nor politics. It is better is to get the government out and let the private sector continue its good work. Those people calling for increased funding could take out their checkbooks and support it. Those who oppose embryonic stem cell research would not be forced to pay for it.”

This is the moral argument against government funding of stem-cell research. But what about the practical ones in favor of such funding? Here are the two I’m wrestling with, along with counterarguments.

1. Government does so much today that it has no business doing, and since this isn’t likely to change appreciably anytime soon, isn’t it better that at least some of our taxes go toward life-giving measures like stem cell research now?

Counterargument: Once government takes an industry into its tentacles, rarely, if ever, does it release it.

2. Isn’t the state the only resource today that can underwrite significant research, a la California’s Proposition 71 ($3 billion over 10 years)? Is stem cell research lucrative enough to draw the top scientists privately?

Counterargument: The Human Genome Project.

Addendum (10/5/2005): Ronald Bailey documents the private sector’s abundant efforts thus far.

July 14th, 2005

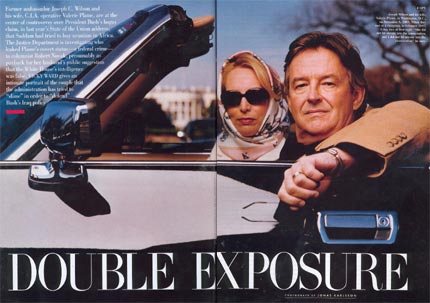

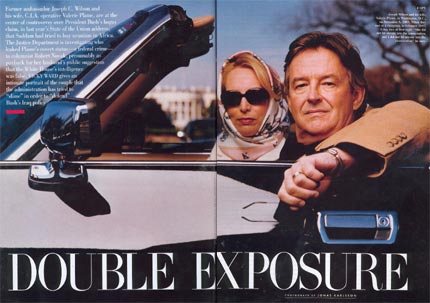

Was Plame, in fact, undercover when she was outed?

Novak says the C.I.A. told him “the exposure of her name might cause ‘difficulties’ if she travels abroad,” but that “[i]t was well-known around Washington that Wilson’s wife worked for the C.I.A. . . . Her name, Valerie Plame, was no secret either, appearing in Wilson’s Who Who’s in America entry.”

Hitchens sneers that she “shuttle[d] dangerously ‘undercover’ between Georgetown and Virginia.”

Clifford May lets slip that he knew her name and identity before Novak’s column outing her: “I learned it from someone who formerly worked in the government and he mentioned it in an offhand manner, leading me to infer it was something that insiders were well aware of.”

On the other hand, Tim Noah uses a “simple test: did her friends and neighbors know she worked for the C.I.A.? They did not. Ergo, she was undercover.”

Addendum (7/17/2005): Joe Wilson admits, “My wife was not a clandestine officer the day that Bob Novak blew her identity.”

Addendum (7/21/2005): Yet it’s not that cut and dry, as Time magazine reports in two articles this week:

[A]s recently as the late 1990s she was working as a nonofficial cover (NOC) officer, one of a select group of operatives within the CIA who are placed in neutral-seeming environments abroad and collect secrets, knowing that the U.S. government will disavow any connection with them should they be caught. NOC officers cost millions of dollars to train and support. As a result of the leak, Plame is no longer able to work undercover.

[W]hile she may no longer have been a clandestine operative [at the time of the leak], she was still under protected status. . . . In the wake of the disclosure, foreign intelligence services were known to have retraced her steps and contacts to discover more about how the CIA operates in their countries.

Addendum (7/24/2005): Or is it, as the New York Times reports?

[Some] former C.I.A. officers say that by 2003 Ms. Wilson’s cover was already thin. Any serious inquiry would have revealed that Brewster Jennings [& Associates, the Boston shell company the C.I.A. set up] was little more than a mailbox. . . . Ms. Wilson . . . had been working for some time at agency headquarters in Langley, Va. And her marriage to a senior American diplomat, Mr. Wilson, ended any pretense of having no government ties.”At that point, she looks, walks and quacks like an overt agency employee,” said Fred Rustmann, a C.I.A. officer from 1966 to 1990, who supervised Ms. Wilson early in her career and calls her “one of the best, an excellent officer.”

Addendum (7/28/2005): Slate explains the different levels of cover in the C.I.A.

July 10th, 2005

Until Joe Wilson’s op-ed appeared on July 6, 2003, the White House had doggedly defended the president’s claim, in his 2003 State of the Union address, that Iraq “recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa.” Not even the announcement, five weeks later, by the director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency that this claim was based on fake documents prompted any retraction. Instead, only after Wilson went public did C.I.A. Director George Tenet, just days later, concede that the uranium reference “should never have been included in the text written for the president.”

Rich:

The pettiness of this retribution [the leaking of the identity of Wilson’s wife] shows just how successfully Mr. Wilson hit the administration’s jugular: his revelation threatened the legitimacy of the war on which both the president’s reputation and reelection campaign had been staked. . . . That the Bush administration would risk breaking the law with an act as self-destructive to American interests as revealing a C.I.A. officer’s identity smacks of desperation.

Addendum (10/2/2005): The Post elaborates:

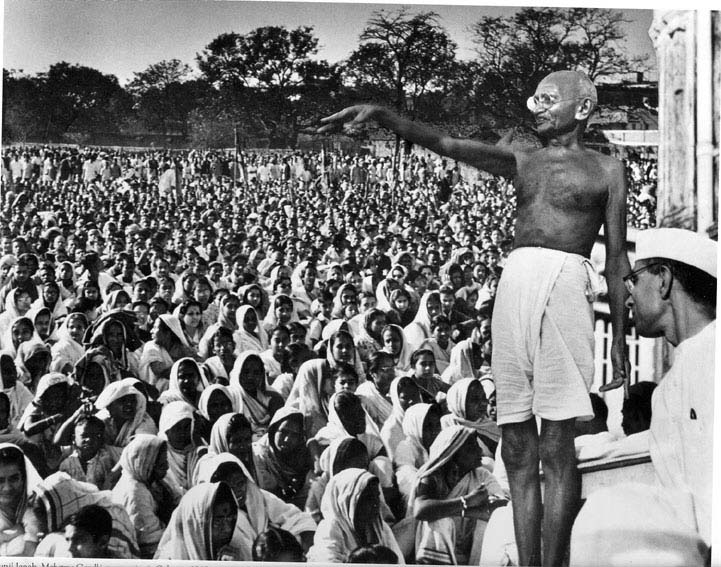

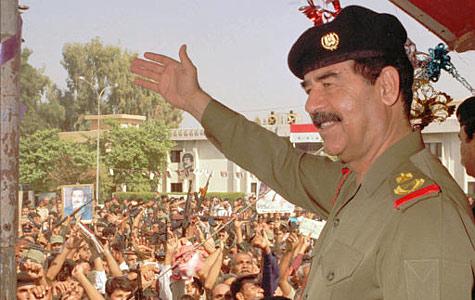

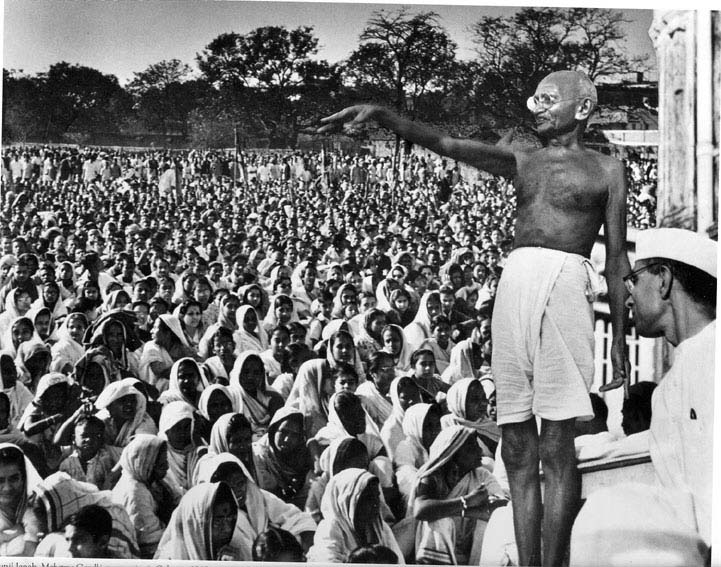

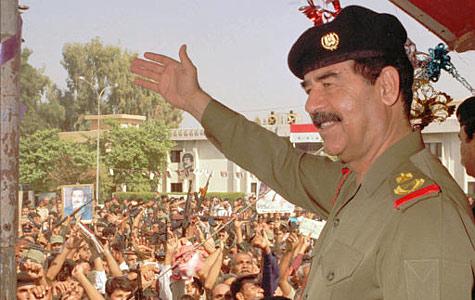

The campaign to discredit Wilson’s accusations came at a critical moment in the Bush presidency. It occurred a few months after the United States invaded Iraq and at a time when Bush, Cheney and the entire administration were under extraordinary pressure to back up their prewar allegations that Iraq had large stockpiles of chemical weapons and was working on a nuclear weapons program. The Niger claim was central to the White House’s rationale for war, and Wilson was on a one-man crusade to disprove it. Early on, his actions caught the eye of the vice president’s office, which was often the emotional and intellectual force pushing the United States to war based on fears of potential weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. Cheney and Libby were intimately involved in building the case for the war, which included warnings that Iraqi President Saddam Hussein was actively pursuing nuclear weapons.

July 7th, 2005

The Los Angeles Times compiles a helpful Q&A (as does the Washington Post). From the Times:

Q: Administration officials signed agreements saying that reporters were free to reveal their identities. Despite that, why won’t reporters name their sources?

A: Miller, Cooper, and other reporters say such “blanket waivers” are not truly voluntary. Officials may have signed them fearing that, if they didn’t, they could be punished or fall under suspicion. Cooper and other journalists said they would talk about their sources only after being convinced that the officials’ willingness to be identified was voluntary, not coerced.

Addendum (7/9/2005): In Matt Cooper’s words:

I am with Judy that these government-issued waivers that the prosecutor has been handing out are not worth the paper they’re written on. . . . It’s coercive. It cannot be considered voluntary.

For C00per, a voluntary waiver must be “specific, personal and unambiguous.”

Addendum (7/15/2005): Floyd Abrams describes the government-issued waivers as “preprinted forms from the Department of Justice that people were instructed to sign by their superiors.”

Another question arises: If Fitzgerald knows who the government officials are, why does he need to question Miller and Cooper?

Answer: To corroborate information he has gathered during his investigation. As a general rule, prosecutors say they would never rely solely on notes taken by someone without also interviewing the note-taker.

July 6th, 2005

1. Judy Miller’s going to jail while Matt Cooper will testify.

2. Cooper and Miller now face four instead the original 18 months of jail, since (1) civil contempt is meant to be coercive rather than punitive, and (2) only four months remain in the term of the current grand jury investigating the case.

3. The real SOB is the leaker or leakers. “Last night I hugged my son goodbye and told him it might be a long time before I see him again,” Cooper told the court. Fortunately, just before today’s hearing, he received, “in somewhat dramatic fashion,” a direct personal communication from his source freeing Cooper from his commitment to keep the source’s identity secret.

July 5th, 2005

Many of us would say that we believe in a philosophy of live and let live. Most of us, however, probably aren’t awakened at 3 a.m. on consecutive weeknights by johns leaving a brothel in the apartment next door. Most of us probably don’t happen upon the sale of cocaine in our driveway.

Indeed, it’s one thing to support decriminalizing prostitution and drugs from an ivory tower. But now that I’ve graduated college, and am living on my own, I wonder if the ban on these so-called victimless crimes is, in fact, reasonable?

A libertarian would argue that what’s immoral should not necessarily be illegal. Paying for sex and getting high may be self-destructive, but both are voluntary choices.

To put it another way, freedom is not coextensive with virtue; vices should not be crimes. In fact, vice often permeates a free society, which imposes on each individual the responsibility to tolerate objectionable behavior. Moreover, who’s sleeping with whom and who’s using what neither harms me nor infringes my rights.

Critics respond that the everyday consequences of decriminalization outweigh abstract notions of unfettered liberty. For instance, after promising riches to young women, pimps keep them tethered to the netherworld through blackmail, inflating their back pay, and even old-fashioned coercion. With respect to drugs, toking up marijuana is allegedly a gateway to shooting up heroin.

These concerns are real, yet they only tell half the truth. In short, the concerns largely arise not because of the crimes themselves, but because of the laws that criminalize the said acts.

It’s less complicated than it sounds.

For instance, contrast black markets, under which prostitution and illegal drug use occur, with free markets. Owing to the dearth of competition and the risk of being busted or extorted, black markets are more expensive and more dangerous than free markets. While black markets incubate graft and omertas, free markets encourage written contracts and public scrutiny. While justice in the black market comes at the barrel of a gun, justice in the free market comes in a courtroom.

Specifically, under current law, both prostitutes and clients lack any legal recourse—if, say, she passes onto him a sexually transmitted disease or if he physically abuses her. Similarly, try getting a refund from a dealer who sold you schwag instead of something hydroponic. Decriminalization would make fraud legally enforceable and shine some much-needed sunlight into these no-man’s-lands.

Indeed, if we were to treat sex and drugs as we do booze, then many hookers and pushers would go legit or go out of business. Instead of employing backseats and back alleys, they could conduct their affairs in offices—in fear not of the FBI but of the IRS.

Furthermore, under current law, two-thirds of the federal government’s budget for the war on drugs goes to incarceration rather than treatment. Surely, however, nonviolent users would be better served by spending time with physicians and psychiatrists than doing time with rapists and robbers. In fact, studies show that prison does little to fight addiction, whereas rehabilitation helps the individual to break his dependency—and thus check the aforementioned gateway.

The world’s oldest trade and perhaps its most profitable one have always outwitted attempts at suppression; no amount of legislation has, or will, defeat man’s yen for pleasure. We would do better as a people and a polity if we recognized this stubborn fact.

July 4th, 2005

Like Dinesh D’Souza, I’ve long thought that Martin Luther King Jr.—given his “I Have a Dream” speech, “that one day my four little children will grow up in a nation where they will be judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character”—would have opposed affirmative action. After all, a colorblind society should reject color-based policies.

But as Eric Foner shows in an essay for Slate from 1996, King most definitely would have supported the hand up:

In Why We Can’t Wait, published in 1963 as the movement to dismantle segregation reached its peak, King observed that many white supporters of civil rights “recoil in horror” from suggestions that blacks deserved not merely colorblind equality but “compensatory consideration.” But, he pointed out, “special measures for the deprived” were a well-established principle of American politics. The GI Bill of Rights offered all sorts of privileges to veterans. Blacks, given their long “siege of denial,” were even more deserving than soldiers of “special, compensatory measures.”King said much the same thing in his last book. Where Do We Go From Here was published in 1967, and in the intervening four years, King’s optimism had given way to foreboding prompted by the emergence of a white backlash and the realization that combating the economic plight of black America would prove far more difficult than eliminating segregation. He called for a series of programs, including full employment and a guaranteed annual income, to uplift the poor of all races. But he saw no contradiction between measures aimed at fighting poverty in general and others that accorded blacks “special treatment” because of the unique injustices they had suffered. “A society that has done something special against the Negro for hundreds of years,” he wrote, “must now do something special for him.”

Further, to compare Jim Crow to affirmative action is wrong and offensive:

Segregation was not simply a matter of racial classification (or “thinking by race,” as Justice Antonin Scalia has written) but part of a complex system of racial subordination whose political, economic, and social elements all reinforced one another. The slogan of the 1963 March on Washington was not colorblind laws but “Jobs and Freedom,” and the movement’s ultimate goal, King insisted, was to “make freedom real and substantive” for black Americans by absorbing them “into the mainstream of American life.”This goal remains as elusive today as it was during King’s lifetime. King’s real heirs are those who, like him, see affirmative action not as a panacea or an end in itself, but as one of many ways to reduce the gap between blacks and the rest of American society bequeathed to us by history.

Where does this leave me? I still oppose affirmative action, since explicitly taking account of race perpetuates racism, but it’s no longer a hot-button issue for me.

July 3rd, 2005

1. According to Newsweek, which quotes Rove’s lawyer, Rove signed a waiver authorizing reporters to testify about their conversations with him. Yet Cooper, who interviewed Rove for the article he coauthored, has refused to discuss his sources save for Libby, who previously waived his confidentiality agreement. Why won’t Cooper tell Fitzgerald what Rove told him?

2. Where are Joseph Wilson and his wife Valerie Plame in all this? Why hasn’t someone asked for their comments?

3. Time Inc. considers its employees’ reportorial notes company property. What’s the Times’s policy?

Addendum (7/5/2005): Scott Shane follows-up on question two with a 1,900-word article in today’s Times.

Addendum (7/6/2005): Tim Noah replies to Shane. Noah also compiles a hyperlinked timeline of Plame’s public appearances and quotes.

Addendum (7/8/2005): Slate’s Explainer columns answers question three:

Who owns a reporter’s notes? It’s a murky issue, and one that hasn’t been fully resolved in court. According to the work-for-hire doctrine prescribed by the federal copyright statute, the employer who paid for the production of a work is considered its owner. In general, any notes, tools, or other materials that were created in the process of producing that work also belong to the employer. Rules for freelancers are somewhat less clear and depend on the exact terms of the contract. Some freelance contracts state explicitly that an article is being produced as a “work for hire.”

Despite the rules laid out by the federal copyright statute, many individual newspapers have their own policies on reporters’ notes. The Wall Street Journal’s parent company declares that “any and all information and other material” obtained by its employees on the job is its exclusive property. A New York Times spokesman says reporters’ notes are their own, by long-standing convention.

July 2nd, 2005

1. Fitzgerald subpoenaed Cooper on the basis on an article he coauthored for Time.com. How does Fitzgerald know that the “government officials” the article refers to spoke with Cooper and not Massimo Calabresi or John Dickerson?

2. How does Fitzgerald know that someone in the know spoke with Judy Miller, who merely conducted interviews on the matter but did not publish an article?

Addendum (7/9/2005): The New York Times answers question two: Fitzgerald has relied on secret evidence in persuading courts to order Miller jailed. He could have learned about her involvement through phone records and by questioning government officials.

Addendum (7/14/2005): Jack Shafer argues that “Fitzgerald seems bent on penalizing Miller for her knowledge of the case rather than for her proximity to the purported crime.”

Additional questions:

3. Why does Time but not the Times face contempt charges?

4. Is Karl Rove Cooper’s deep throat?

Addendum (11/21/2005): Time answers question three: “Miller . . . was originally subpoenaed along with the Times. After the newspaper said it had no relevant documents to hand over and that Miller’s notes—and the decision whether to turn them over—belonged to her alone, the court pursued only the subpoena against Miller. . . . In the Cooper case, the prosecutor went after e-mails and other information stored on computers owned by Cooper’s employer, Time Inc., which was subpoenaed and held in contempt when it refused to turn over the documents.”

June 26th, 2005

The New York Times reports: “At a moment when France is suffering from an unemployment rate of more than 10 percent, and Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin is waging what he calls a 100-day battle to combat it, [Adamski’s trip] is an effort to assure the French that Polish workers have no intention of stealing their jobs. Even if they wanted to, they could not. Under the treaty that allowed Poland and nine other countries to join the European Union last year, older members of the union can restrict access to their labor markets for up to seven years. Only Britain, Ireland and Sweden have allowed in workers from the new members.”

To be sure, the U.S. also practices nativism, particularly with respect to H-1B visas, which companies like Microsoft use to hire skilled professionals.

Fortunately, we still have people like Microsoft C.E.O. Bill Gates, who recently called the H-1B caps “almost a case of a centrally controlled economy.”

Fareed Zakaria crystallizes the point: “Every visa officer today lives in fear that he will let in the next Mohamed Atta. As a result, he is probably keeping out the next Bill Gates.”

Harry Binswanger draws the philosophical lesson, in an essay titled “‘Buy American’ Is Un-American”: “Economic nationalism, like racism, means judging men and their products by the group from which they come, not by merit.”

May 2nd, 2005

In 2002, Denzel Washington won an Oscar for his performance in Training Day, becoming the first black man to win Best Actor. Yet breaking with conventional wisdom, especially in Hollywood, Washington declared his race to be irrelevant:

“[T]omorrow, when you report this,” he said, “why not just say Denzel won the Oscar, and not mention that he is black.”

In an interview last week with Time, the rapper Nelly echoed these admirable thoughts:

Q: You co-own a NASCAR team, and you’ve done a duet with Tim McGraw. Are you trying to break racial stereotypes in entertainment?

A: I’m trying to make money, sweetheart. I’m an entrepreneur.

Incidentally, Nell’s line echoes one from the 2000 movie, Boiler Room: “There’s no honor in taking that after school job at Mickey Dee’s. Honor’s in the dollar, kid.”

Addendum (12/21/2005): The actor Morgan Freeman echoes Washington in a recent interview on 60 Minutes:

“[Freeman] says the only way to get rid of racism is to ‘stop talking about it.’

“The actor says he believes the labels ‘black’ and ‘white’ are an obstacle to beating racism.

“‘I am going to stop calling you a white man and I’m going to ask you to stop calling me a black man,’ Freeman says.

Addendum (6/14/2011): About a year ago before she was named the top editor of the New York Times, Jill Abramson was asked for her thoughts on ascending to this position, in which case she’d be the first woman in the paper’s history to do so. Her answer is spot-on:

“I don’t dwell on it … I think it would be a healthy, nice thing for the country. It is meaningful to have women in positions of leadership at important institutions in society. But, you know, there are wonderful male editors in this place who are just as capable as I am, and they could run this place exquisitely well. If it happens, it happens, if it doesn’t, it doesn’t.”

May 1st, 2005

This isn’t a 404 error; the page you’re looking for isn’t missing. I just moved it—in fact, I created a microsite for it.

April 15th, 2005

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it’s the only thing that has.”

So said the anthropologist Margaret Mead. At least that’s what most of us have been led to believe.

But according to the Institute for Intercultural Studies, this quotation cannot be verified. “[W]e have been unable to locate when and where [this quote] was first cited . . . We believe it probably came into circulation through a newspaper report of something [Mead] said spontaneously and informally. We know . . . that it was firmly rooted in her professional work and that it reflected a conviction that she expressed often, in different contexts and phrasings.”

Related: “The Duties of Educated Young People.”

April 9th, 2005

Here’s a letter I recently wrote to the New York Times. Since it hasn’t run yet, I figure it’s safe to publish it myself.

The New York Times editorial board says it’s “intolerable” that anti-abortion pharmacists refuse to dispense birth control pills. I am as staunch a supporter of abortion rights as they come, but for the same reason I equally champion property rights: both represent the inalienable right of human autonomy. Just as no one should tell a woman how to dispose of her body, so no one should tell a businessman how to conduct his practice.

If one of his employees disagrees, that is between employee and employer, and if necessary, a court, to determine if a contract was breached. If outsiders disagree, we can disseminate local lists of where not to shop, and are perfectly free to shop elsewhere ourselves. The answer is not legislation, forcing our morals on others, but patronage, noncoercively using our principles to induce change.

Addendum (4/29/05): See this debate between David Boaz, Executive Vice President of the Cato Institute, and Judy Waxman, Vice President and Director of Health and Reproductive Rights at the National Women’s Law Center.

Scholars “use an intellectual scalpel…