Search results for the tag, "Media"

July 28th, 2009

Some editors balk at publishing details of their reporters’ fruitless attempts to interview a source. So as to let the story speak for itself, not appear whiny, and/or not burn a bridge, they prefer to summarize such sausage making through boilerplate. “Repeated phone calls and e-mails were not returned,” is a line I often read.

But when the subject of a major story in a major magazine continually stonewalls and reneges, the publication does its readers a diservice by omitting these salient details. Thankfully, in its current issue, Vanity Fair bucks this trend, and allows its contributor, Nina Munk, to divulge her stymied efforts to report on Harvard’s shrinking endowment.

As you may have guessed by now, Harvard refused to cooperate when I was reporting this story. At first, the university’s public-relations apparatus ignored me. Week after week, e-mail after e-mail, I’d be assured that someone or someone else was unavailable—in meetings, or on vacation, or away from his desk, or out of the office, ill. When I did manage to track someone down, I was thrown a sop of evasive prose. (“I don’t feel we’ve made a decision about how to best engage for your piece,” the vice president for public affairs told me in an e-mail.) A formally scheduled interview with the dean of the business school was canceled at the very last minute. (“Glitch” was the subject heading of an e-mail informing me that the meeting was off.) Even requests for basic, public financial information were bungled. When I asked him a simple question about Harvard’s debt, one of the university’s many communications directors stonewalled: “I’m not a numbers person at all,” he said, wide-eyed.

No doubt, most reporters will empathize. As readers, we should too.

October 4th, 2005

In naming President Bush Person of the Year 2004, Time magazine received both Oval Office access for its photographer and a second interview with the president in less than four months (the previous story was in August, apropos the Republican National Convention).

Reading such exclusives inevitably prompts one question: in order to attain—and, more important, to maintain—such access, do journalists temper their coverage of the given subject? After all, if they are too critical of, say, the Iraq war, they risk alienating Bush, who reportedly snubbed Peter Jennings, who interviewed the last four sitting presidents, for that reason.

Indeed, the press critic Michael Massing describes today’s relationship between high-powered reporters and the White House this way:

“Karen D. Young, one of the top editors [at the Washington Post], said . . . ‘Let’s face it, we are basically a mouthpiece for whatever administration is in power’. . . . It’s a major admission of how the major media have in fact served as conveyor belts. . . . have gotten so much toward a position to be handmaidens to the people in power. . . . [Take,] for instance, Pentagon correspondents flying with Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowitz to Iraq and Afghanistan. They want to be on the plane. They know if they write things that are too critical, they’re not going to get seats there. . . . Your career can be shredded if you speak out too much against those in power.”

On the other hand, if a journalist is too mealy-mouthed, he sacrifices fairness and balance. See Judy Miller vis-à-vis Ahmed Chalabi.

How, then, do and how should journalists draw the line between closeness to sources and responsibility to readers?

One suggestion: Charles Krauthammer, Washington Post columnist, Time essayist, contributing editor to the New Republic and Weekly Standard, and a member of the President’s Council on Bioethics.

Granted, Krauthammer opines rather than reports, which means his job doesn’t depend on cultivating sources. But he’s also one of the most eloquent and prominent neoconservatives, and, as such, has consulted with the Bush administration. (In fact, he was criticized for failing to disclose his meeting with White House officials regarding the president’s second inaugural.)

And yet, during the early days of Hurricane Katrina, Krauthammer didn’t hesitate to call W “[l]ate, slow, and simply out of tune with the urgency and magnitude of the disaster.” He continues:

“His flyover on the way to Washington was the worst possible symbolism. And his Friday visit was so tone-deaf and politically disastrous that he had to fly back three days later.”

The point: criticize the presidency, not the president.

Postscript (10/25/2005): Or follow Krauthammer’s conservative colleague on the Post op-ed page, George Will, who in a recent column said this about the president and Harriet Miers: “He has neither the inclination nor the ability to make sophisticated judgments about competing ap-proaches to construing the Constitution. Few presidents acquire such abilities in the course of their pre-presidential careers, and this president particularly is not disposed to such reflections.”

Postscript (10/26/2005): Hmm…

Postscript (10/29/2005): The Los Angeles Times reports: “On one occasion, the office [of the vice president] prohibited a reporter from traveling with Cheney aboard Air Force Two, because the vice president’s daughter said Cheney was unhappy with that newspaper’s coverage.”

August 10th, 2005

Those who berate Judy Miller for her coverage of Iraq’s alleged W.M.D. should remember that Miller’s copy was only one aspect of any final article, which, as former New York Times Public Editor Daniel Okrent wrote in a different context, “is the collaborative product of reporter, editor, copy editor, desk or department head, and sometimes, the anointing ministrations of a masthead editor.”

Addendum: Steve Engleberg, former head of investigations at the Times, tells Editor and Publisher that he puts primary blame on the papers’ editors for printing Miller’s stories on WMD.

We should also remember that some of Miller’s worst articles were coauthored; see here and here.

Addendum (12/16/2005): Ken Auletta:

Miller, for her part, asked why no one blamed editors like [former executive editor Howell] Raines, and others, “who knew all of my sources.” (Raines, in an e-mail, said, “I did not know Judy’s sources. At the time, I followed the customary Times practice of relying on the supervising desk editor—in this case, most often the Washington editor and the foreign editor—to make sure the sourcing on the stories they handled was correct. I questioned reporters directly on some stories out of the Pentagon, but, to my regret, I did not do so on these stories. As many journalism critics have noted, the Times has yet to reveal what editors among present staff members were directly involved in assigning and editing Judy Miller’s stories. Scapegoating Judy or anyone else does not erase their responsibility to tell their readers the full truth in this matter.”)

July 17th, 2005

1. Doug Clifton, editor of the Cleveland Plain Dealer:

[T]wo stories of profound importance languish in our hands. The public would be well served to know them, but both are based on documents leaked to us by people who would face deep trouble for having leaked them. Publishing the stories would almost certainly lead to a leak investigation and the ultimate choice: talk or go to jail.

Because talking isn’t an option and jail is too high a price to pay, these two stories will go untold for now.

Read more from Editor and Publisher and the New York Times.

2. The Washington Post:

Time reporters have said that at least two sources have told them they would no longer provide information because the company turned over [Cooper’s] documents.

Addendum (7/23/2005): Pearlstine confirms, to the Senate Judiciary Committee, that Time reporters have received e-mails from sources saying they no longer trust the magazine.

Addendum (10/1/2005): Jim Kelly, Time’s managing editor, tells the New York Times, “Looking at what we’ve managed to publish since [Cooper testified], it is very hard for me to point to any damage that was done to Time magazine with its sources.”

July 15th, 2005

On July 6, having received an hour earlier, “in somewhat dramatic fashion . . . an express personal release from my source,” Matt Cooper agreed to testify. But as the New York Times reports, that source—Karl Rove—never gave Cooper the release himself. Rather, the release resulted from a “frenzied series of phone calls initiated that morning” by Cooper’s lawyer, Richard Sauber, to Karl Rove’s lawyer, Robert Luskin, and which involved the special prosecutor.

Here’s what happened (with additional reporting from Editor and Publisher). On his way back from Alaska to Washington on the night of July 5, Sauber passed through Chicago at 6 a.m., where he picked up the Times and the Wall Street Journal. Back on the phone, he read an article in the Journal that quoted Luskin as saying, “Mr. Rove hasn’t asked any reporter to treat him as a confidential source in the matter. So if Matt Cooper is going to jail to protect a source, it’s not Karl he’s protecting.”

Sauber immediately called Cooper from the plane, and they agreed to ask Luskin for a specific release from Rove. “I think we should take a shot,” Cooper recalled. “I said, ‘Yes, it’s an invitation.’”

When he landed in Washington, Sauber called Luskin, who called back at around 12:30 p.m.—an hour and half before court re-adjourned. Luskin dictated a waiver to Sauber, who then sent it Luskin, who signed and returned it at around 1 p.m.

The new waiver said only that Rove “affirm[ed]” his previous, blanket waiver, but it specified “any conversation he [Rove] may have had with Matthew Cooper of Time magazine during the month of July 2003.”

July 14th, 2005

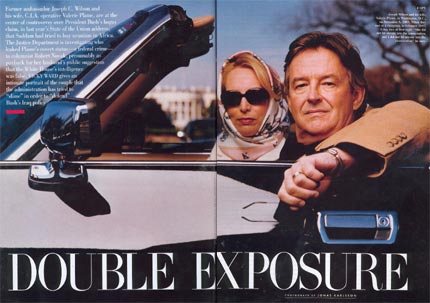

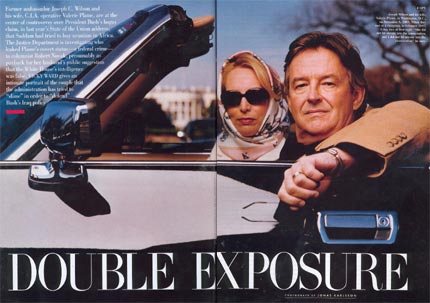

Was Plame, in fact, undercover when she was outed?

Novak says the C.I.A. told him “the exposure of her name might cause ‘difficulties’ if she travels abroad,” but that “[i]t was well-known around Washington that Wilson’s wife worked for the C.I.A. . . . Her name, Valerie Plame, was no secret either, appearing in Wilson’s Who Who’s in America entry.”

Hitchens sneers that she “shuttle[d] dangerously ‘undercover’ between Georgetown and Virginia.”

Clifford May lets slip that he knew her name and identity before Novak’s column outing her: “I learned it from someone who formerly worked in the government and he mentioned it in an offhand manner, leading me to infer it was something that insiders were well aware of.”

On the other hand, Tim Noah uses a “simple test: did her friends and neighbors know she worked for the C.I.A.? They did not. Ergo, she was undercover.”

Addendum (7/17/2005): Joe Wilson admits, “My wife was not a clandestine officer the day that Bob Novak blew her identity.”

Addendum (7/21/2005): Yet it’s not that cut and dry, as Time magazine reports in two articles this week:

[A]s recently as the late 1990s she was working as a nonofficial cover (NOC) officer, one of a select group of operatives within the CIA who are placed in neutral-seeming environments abroad and collect secrets, knowing that the U.S. government will disavow any connection with them should they be caught. NOC officers cost millions of dollars to train and support. As a result of the leak, Plame is no longer able to work undercover.

[W]hile she may no longer have been a clandestine operative [at the time of the leak], she was still under protected status. . . . In the wake of the disclosure, foreign intelligence services were known to have retraced her steps and contacts to discover more about how the CIA operates in their countries.

Addendum (7/24/2005): Or is it, as the New York Times reports?

[Some] former C.I.A. officers say that by 2003 Ms. Wilson’s cover was already thin. Any serious inquiry would have revealed that Brewster Jennings [& Associates, the Boston shell company the C.I.A. set up] was little more than a mailbox. . . . Ms. Wilson . . . had been working for some time at agency headquarters in Langley, Va. And her marriage to a senior American diplomat, Mr. Wilson, ended any pretense of having no government ties.”At that point, she looks, walks and quacks like an overt agency employee,” said Fred Rustmann, a C.I.A. officer from 1966 to 1990, who supervised Ms. Wilson early in her career and calls her “one of the best, an excellent officer.”

Addendum (7/28/2005): Slate explains the different levels of cover in the C.I.A.

July 7th, 2005

The Los Angeles Times compiles a helpful Q&A (as does the Washington Post). From the Times:

Q: Administration officials signed agreements saying that reporters were free to reveal their identities. Despite that, why won’t reporters name their sources?

A: Miller, Cooper, and other reporters say such “blanket waivers” are not truly voluntary. Officials may have signed them fearing that, if they didn’t, they could be punished or fall under suspicion. Cooper and other journalists said they would talk about their sources only after being convinced that the officials’ willingness to be identified was voluntary, not coerced.

Addendum (7/9/2005): In Matt Cooper’s words:

I am with Judy that these government-issued waivers that the prosecutor has been handing out are not worth the paper they’re written on. . . . It’s coercive. It cannot be considered voluntary.

For C00per, a voluntary waiver must be “specific, personal and unambiguous.”

Addendum (7/15/2005): Floyd Abrams describes the government-issued waivers as “preprinted forms from the Department of Justice that people were instructed to sign by their superiors.”

Another question arises: If Fitzgerald knows who the government officials are, why does he need to question Miller and Cooper?

Answer: To corroborate information he has gathered during his investigation. As a general rule, prosecutors say they would never rely solely on notes taken by someone without also interviewing the note-taker.

July 3rd, 2005

1. According to Newsweek, which quotes Rove’s lawyer, Rove signed a waiver authorizing reporters to testify about their conversations with him. Yet Cooper, who interviewed Rove for the article he coauthored, has refused to discuss his sources save for Libby, who previously waived his confidentiality agreement. Why won’t Cooper tell Fitzgerald what Rove told him?

2. Where are Joseph Wilson and his wife Valerie Plame in all this? Why hasn’t someone asked for their comments?

3. Time Inc. considers its employees’ reportorial notes company property. What’s the Times’s policy?

Addendum (7/5/2005): Scott Shane follows-up on question two with a 1,900-word article in today’s Times.

Addendum (7/6/2005): Tim Noah replies to Shane. Noah also compiles a hyperlinked timeline of Plame’s public appearances and quotes.

Addendum (7/8/2005): Slate’s Explainer columns answers question three:

Who owns a reporter’s notes? It’s a murky issue, and one that hasn’t been fully resolved in court. According to the work-for-hire doctrine prescribed by the federal copyright statute, the employer who paid for the production of a work is considered its owner. In general, any notes, tools, or other materials that were created in the process of producing that work also belong to the employer. Rules for freelancers are somewhat less clear and depend on the exact terms of the contract. Some freelance contracts state explicitly that an article is being produced as a “work for hire.”

Despite the rules laid out by the federal copyright statute, many individual newspapers have their own policies on reporters’ notes. The Wall Street Journal’s parent company declares that “any and all information and other material” obtained by its employees on the job is its exclusive property. A New York Times spokesman says reporters’ notes are their own, by long-standing convention.

July 2nd, 2005

1. Fitzgerald subpoenaed Cooper on the basis on an article he coauthored for Time.com. How does Fitzgerald know that the “government officials” the article refers to spoke with Cooper and not Massimo Calabresi or John Dickerson?

2. How does Fitzgerald know that someone in the know spoke with Judy Miller, who merely conducted interviews on the matter but did not publish an article?

Addendum (7/9/2005): The New York Times answers question two: Fitzgerald has relied on secret evidence in persuading courts to order Miller jailed. He could have learned about her involvement through phone records and by questioning government officials.

Addendum (7/14/2005): Jack Shafer argues that “Fitzgerald seems bent on penalizing Miller for her knowledge of the case rather than for her proximity to the purported crime.”

Additional questions:

3. Why does Time but not the Times face contempt charges?

4. Is Karl Rove Cooper’s deep throat?

Addendum (11/21/2005): Time answers question three: “Miller . . . was originally subpoenaed along with the Times. After the newspaper said it had no relevant documents to hand over and that Miller’s notes—and the decision whether to turn them over—belonged to her alone, the court pursued only the subpoena against Miller. . . . In the Cooper case, the prosecutor went after e-mails and other information stored on computers owned by Cooper’s employer, Time Inc., which was subpoenaed and held in contempt when it refused to turn over the documents.”

April 4th, 2005

In the 16 months between Sept. 11, 2001, and the Iraq war—despite considerable efforts to entangle Saddam Hussein in the former[1]—hawks came up seriously short. Consequently, neither of the Bush administration’s two most publicized arguments for the war—the President’s State of the Union address and Secretary of State Colin Powell’s presentation to the U.N. Security Council—even mentioned the evidence allegedly implicating Baghdad in our day of infamy. Lest we misconstrue the subtext, on Jan. 31, 2003, Newsweek asked the President specifically about a 9/11 connection to Iraq, to which Bush replied, “I cannot make that claim.”

And yet, seven weeks later, a few days before the war began, the Gallup Organization queried 1,007 American adults on behalf of CNN and USA Today. The pollsters asked, “Do you think Saddam Hussein was personally involved in the Sept. 11th (2001) terrorist attacks (on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon), or not” Fifty-one percent of respondents said yes, 41% said no, and 8% were unsure. What accounts for this discrepancy between the American people and their government

Many blame the media; indeed, it has become a cliché, in the title of a recent book by Michael Massing, to say of antebellum reporting, Now They Tell Us (New York Review of Books, 2004). Such facileness, however, confuses coverage of Iraq’s purported “weapons of mass destructions”—which as some leading newspapers and magazines have since acknowledged was inadequately skeptical[2]—with coverage of Iraqi-al-Qaeda collaboration, which was admirably exhaustive.

Instead, two answers arise. First, the current White House is perhaps the most disciplined in modern history in staying on machine. Although the President denied the sole evidence tying Saddam to 9/11—an alleged meeting in Prague between an Iraqi spy and the ringleader of the airline hijackers in April 2001—the principals of his administration consistently beclouded and garbled the issue. As Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld told Robert Novak in May 2002, “I just don’t know” whether there was a meeting or not. Or as George Tenet told the congressional Joint Inquiry on 9/11 a month later (though not unclassified until Oct. 17, 2002), the C.I.A. is “still working to confirm or deny this allegation.” Or as National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice told Wolf Blitzer in September 2002, a month before Congress would vote to authorize the war, “We continue to look at [the] evidence.” Or as Vice President Richard Cheney told Tim Russert the same day, “I want to be very careful about how I say this. . . . I think a way to put it would be it’s unconfirmed at this point.” Indeed, a year later—even after U.S. forces in Iraq had arrested the Iraqi spy, who denied having met Mohammed Atta—Cheney continued to sow confusion: “[W]e’ve never been able to . . . confirm[] it or discredit[] it,” he asserted. “We just don’t know.”

A second hypothesis is that while Iraq had nothing to do with 9/11, it did have a relationship with al Qaeda. Never mind that at best the relationship was tenuous, that there was nothing beyond some scattered, inevitable feelers. That Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden had been in some sort of contact since the early 1990s allowed the Bush administration to shamelessly conflate their activities pertaining to 9/11 and those outside 9/11.

In this way, as late as October 2004, in his debate with John Edwards during the presidential campaign, Dick Cheney continued to insist that Saddam had an “established relationship” with al Qaeda. Senator Edwards’s reply was dead-on: “Mr. Vice President, you are still not being straight with the American people. There is no connection between the attacks of September 11 and Saddam Hussein. The 9/11 Commission said it. Your own Secretary of State said it. And you’ve gone around the country suggesting that there is some connection. There’s not.”

Two months ago, CBS News and the New York Times found that 30 percent of Americans still believe that Saddam Hussein was “personally involved in the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.” Sixty-one percent disagreed. This is certainly an improvement; yet the public is not entirely to blame. Nor is the Fourth Estate.

Rather, the problem lies primarily with the Bush administration. Andrew Card, George W. Bush’s Chief of Staff, explained it best. “I don’t believe you,” he told Ken Auletta of the New Yorker, “have a check-and-balance function.” In an interview, Auletta elaborated: “[T]hey see the press as just another special interest.” This is the real story of the run-up to the Iraq war: not a press that is cowed or bootlicking, but a government that treats the press with special scorn and sometimes simply circumvents it. As columnist Steve Chapman put it, the administration’s policy was “never to say anything bogus outright when you can effectively communicate it through innuendo, implication and the careful sowing of confusion.”

Indeed, now that we are learning more stories of propaganda from this administration—$100 million to a P.R. firm to produce faux video news releases; White House press credentials to a right-wing male prostitute posing as a reporter; payolas for two columnists and a radio commentator to promote its policies—the big question isn’t about the supposed failings of the press. The question is about the ominously expanding influence of state-sponsored disinformation.

Footnotes

[1] For instance, on 10 separate occasions Donald Rumsfeld asked the C.I.A. to investigate Iraqi links to 9/11. Daniel Eisenberg, “‘We’re Taking Him Out,’” Time, May 13, 2002, p. 38.

Similarly, Dick Cheney’s chief of staff, I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, urged Powell’s speechwriters to include the Prague connection in his U.N. address. Dana Priest and Glenn Kessler, “Iraq, 9/11 Still Linked by Cheney,” Washington Post, September 29, 2003.

[2] See, for instance, The Editors, “Iraq: Were We Wrong,” New Republic, June 28, 2004; [Author unspecified], “The Times and Iraq,” New York Times, May 26, 2004; and Howard Kurtz, “The Post on W.M.D.: An Inside Story,” Washington Post, August 12, 2004.

April 19th, 2004

A version of this blog post was awarded the Hamilton College 2005 Cobb Essay Prize, appeared in the Utica Observer-Dispatch (April 19, 2004), and was noted on the Hamilton College Web site (April 21, 2004).

Most of us trust that what we read, watch or hear from well-established news organization is trustworthy. But trustworthiness depends on the source—not only the organization, but also the origin of information. For without freedom one cannot report the news freely. It is therefore fraudulent for a news agency to operate in a dictatorship without disclosure.

What constitutes a dictatorship? First, if independent media exist, the state aggressively censors them. After all, news doesn’t mean much if citizens are privy only to propaganda. Second, if candidates for political office exist, the state shackles their activities. After all, news doesn’t mean much if the opposition is nonexistent. Third, the state cows its citizens. After all, news doesn’t mean much if people are afraid to speak.

As Iraqis and U.S. marines toppled the massive statue of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad two years ago, Eason Jordan, chief news executive of the Cable News Network (CNN), penned an op-ed for the New York Times. The headline was its own indictment: “The News We Kept to Ourselves.” For the past 12 years, Jordan confessed, there were “awful things that could not be reported because doing so would have jeopardized the lives of Iraqis, particularly those on our Baghdad staff.” This much is inarguable: the Hussein regime expertly terrorized, if not executed, any Iraqi courageous enough to slip a journalist an unapproved fact. Jordan relates one particularly horrifying story: “A 31-year-old Kuwaiti woman, Asrar Qabandi, was captured by Iraqi secret police . . . for ‘crimes,’ one of which included speaking with CNN on the phone. They beat her daily for two months, forcing her father to watch. In January 1991, on the eve of the [first] American-led offensive, they smashed her skull and tore her body apart limb by limb. A plastic bag containing her body parts was left on the doorstep of her family’s home.”[1]

As for the journalists, had one been “lucky” enough to gain a visa to Iraq, one then received a minder. An English-speaking government shadow, the minder severely circumscribed a journalist’s travels to a regime-arranged itinerary. Franklin Foer of the New Republic describes one typical account: when a correspondent unplugged the television in his hotel room, a man knocked on his door a few minutes later asking to repair the “set.” Another correspondent described an anti–American demonstration, held in April 2002 in Baghdad, to celebrate Saddam’s 65th birthday. When her colleagues turned on their cameras, officials dictated certain shots and, with bullhorns, instructed the crowd to increase the volume of their chants. Had the regime deemed one’s reports to be too critical, like those of recently retired New York Times reporter Barbara Crossette or CNN anchor Wolf Blitzer, it simply revoked one’s visa or shut down one’s bureau, or both.[2] Of course, this all depends on the definition of “critical”; referring to “Saddam,” and not “President Saddam Hussein,” got you banned for “disrespect.” At least until an Eason Jordan could toady his way back in.

And yet CNN advertises itself as the “most trusted name in news.” Truth, however, as the American judicial oath affirms, consists of the whole truth and nothing but the truth; what one omits is equally important as what one includes. Thus, to have reported from Saddam’s Iraq as if Tikrit were Tampa was to abdicate a journalist’s cardinal responsibility. Indeed, if journalists in Iraq could not have pursued, let alone publish, the truth, they should not have not been concocting the grotesque lie that they could, and were. Any Baghdad bureau under Saddam is a Journalism 101 example of double-dealing. And any news agency worthy of the title wouldn’t have had a single person inside Iraq—at least officially. Instead, journalists could have scoured Kurdistan or Kuwait, even London, where many recently arrived Iraqis can talk without fear of death. According to former C.I.A. officer Robert Baer, who was assigned to Iraq during the Gulf War, Amman, the capitol of Jordan, is a virtual pub for Iraqi expatriates.[3]

Why, then, were the media in Iraq? As columnist Mark Steyn observes, “What mattered to CNN was not the two-minute report of rewritten Saddamite press releases but the sign off: ‘Jane Arraf, CNN, Baghdad.’”[4] Today’s media today access above everything and at any cost—access to the world’s most brutal sovereign of the last 30 years and his presidential palaces built with blood money, and at the costs of daily beatings, skull-smashings and limb-severings. Dictators, of course, understand this dark hunger, and for allowing one to stay in hell, they demand one’s soul, or unconditional obsequiousness. Thus did CNN become a puppet for disinformation, broadcasting the Baath Party line to the world without so much as innuendo that “Jane Arraf, CNN, Baghdad” was not the same as “Jane Arraf, CNN, Washington.” In this way, far from providing anything newsworthy, let alone protecting Iraqis, the media’s presence there only lent legitimacy and credibility to Saddam’s dictatorship.

Alas, dictatorship neither begins nor ends with Iraq. According to Freedom House, America’s oldest human rights organization, comparable countries today include Burma, China, Cuba, Iran, Libya, North Korea, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria, Uzbekistan and Vietnam.[5] How should we read articles with these datelines? In judging the veracity of news originating from within a dictatorship, the proper principle is caveat legens—reader beware. As Hamilton College history professor Alfred Kelly explains in a guidebook for his students, train yourself to think like a historian. Ask questions such as: Under what circumstances did the writer report? How might those circumstances, like fear of censorship or the desire to curry favor or evade blame, have influenced the content, style or tone? What stake does the writer have in the matters reported? Are his sources anonymous? What does the text omit that you might have expected it to include?[6] You need not be a conspiracy theorist to recognize the value of skepticism.

Footnotes

[1] Eason Jordan, “The News We Kept to Ourselves,” New York Times, April 11, 2003.

[2] Franklin Foer, “How Saddam Manipulates the U.S. Media: Air War,” New Republic, October 2002.

[3] Franklin Foer, “How Saddam Manipulates the U.S. Media: Air War,” New Republic, October 2002.

[4] Mark Steyn, “All the News That’s Fit to Bury,” National Post (Canada), April 17, 2003.

[5] As quoted in Joseph Loconte, “Morality for Sale,” New York Times, April 1, 2004.

[6] Alfred Kelly, Writing a Good History Paper, Hamilton College Department of History, 2003.

Bibliography

Chinni, Dante, “About CNN: Hold Your Fire,” Christian Science Monitor, April 17, 2003.

Collins, Peter, “Corruption at CNN,” Washington Times, April 15, 2003.

—, “Distortion by Omission,” Washington Times, April 16, 2003.

Da Cunha, Mark, “Saddam Hussein’s Real Ministers of Disinformation Come Out of the Closet,” Capitalism Magazine, April 14, 2003.

Fettmann, Eric, “Craven News Network,” New York Post, April 12, 2003.

Foer, Franklin, “CNN’s Access of Evil,” Wall Street Journal, April 14, 2003.

—, “How Saddam Manipulates the U.S. Media: Air War,” New Republic, October 2002.

Glassman, James K., “Sins of Omission,” TechCentralStation.com, April 11, 2003.

Goodman, Ellen, “War without the ‘Hell,’” Boston Globe, April 17, 2003.

Kelly, Alfred, Writing a Good History Paper, Hamilton College Department of History, 2003.

Jacoby, Jeff, “Trading Truth for Access?” Jewish World Review, April 21, 2003.

Jordan, Eason, “The News We Kept to Ourselves,” New York Times, April 11, 2003.

Loconte, Joseph, “Morality for Sale,” New York Times, April 1, 2004.

de Moraes, Lisa, “CNN Executive Defends Silence on Known Iraqi Atrocities,” Washington Post, April 15, 2003.

Smith, Rick, “CNN Should Scale Back Chumminess with Cuba,” Capitalism Magazine, May 8, 2003.

Steyn, Mark, “All the News That’s Fit to Bury,” National Post (Canada), April 17, 2003.

Tracinski, Robert W., “Venezuela’s Countdown to Tyranny,” Intellectual Activist, April 2003.

Walsh, Michael, “Here Comes Mr. Jordan,” DuckSeason.org, April 11, 2003.

Addendum

Newsweek’s Christopher Dickey recently observed that the “media marketplace . . . long ago concluded [that] having access to power is more important speaking truth to it.”

Scholars “use an intellectual scalpel…