Search results for the tag, "Education"

September 17th, 2007

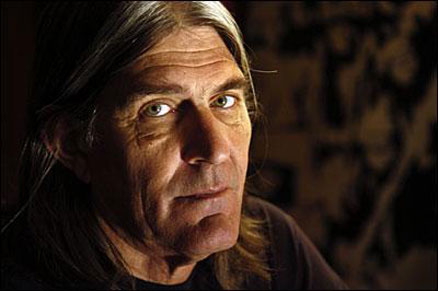

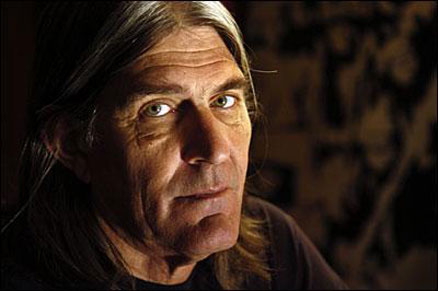

A few days ago, I received the 2007-08 edition of Hamilton College’s “viewbook,” which my alma mater sends to prospective students and alumni. The pamphlet contains a wonderful essay by Professor of History Al Kelly on the art of pedagogy. Since it’s not online, I’ll excerpt the essay here:

“I’ve learned that what sticks with students could never get into my notes: the way I think about things; the way I bring facts to bear; the way I call the obvious into question; the way I read; the way I tear apart a sentence; the way I try to jolt them into seeing the world differently. The students can look up the Ems Dispatch. But I flatter myself that they cannot look up any of those really important things that I try to teach them. If I do my job well . . . I lead them along the path from what can be Googled into the land of what cannot be Googled.

“What long-term effects do I want my history teaching to have on my students? I’d like them to have a hard head and a soft heart. I’d like them to be wise; to maintain perspective; to puncture fatuous claims of novelty; to write with skill and grace; to judge only after they have empathized; and to develop what the Germans learned the hard way to call ‘civil courage.’ Faced—God forbid—with a totalitarian regime, my former students would, I hope, be among the first arrested.

April 7th, 2007

Newt Gingrich takes to the op-ed page of the LA Times today to clarify his YouTubed remark equating Spanish with “the language of living in a ghetto.” His premise is as follows:

Mastering the language of a country opens doors of opportunity. . . . In the United States, English is by no means our only language, but it is the language of economic success and upward mobility.

This is so self-evident, I’m constantly dumbfounded when I run into someone (say, a server in the capitol building cafeteria, as I did yesterday) who shrugs and says, “No hablo Inglés.”

Of course, the ignorance of such people is their loss, not mine, and ignorance does not threaten me. What does threaten me, for instance, are multilingual ballots.

Why should ballots be unilingual? Because what makes America unique is our ability to assimilate immigrants. A common tongue gives us unity and thus strength. As Charles Krauthammer has argued,

The key to assimilation . . . is language. The real threat to the United States is not immigration per se but bilingualism and, ultimately, biculturalism. Having grown up in Canada, where a language divide is a recurring source of friction and fracture, I can only wonder at those who want to duplicate that plague in the United States. . . .

The way to prevent European-like immigration catastrophes is to turn every immigrant—and most surely his children—into an [English-speaking] American.

Indeed, this is why bilingual education—that is, being taught (usually in Spanish) while being gradually taught English—is misguided. As Krauthammer notes, “It delays assimilation by perhaps a full generation.”

To be sure, had I learned espanol while learning English (instead of blowing off classes in the former in high school), I bet I’d be fluent today. Research shows that learning a language is easiest when you’re young and the mind is sponge-like. Moreover, in part because of our geographic insulation, Americans are less worldly than our European counterparts, among whom bilingualism is the rule rather the exception. In the age of interconnectedness, speaking only one tongue—even if it’s the global one—surely puts us at a competitive disadvantage.

These objections are valid, but can both be addressed via immersion classes, instead of bilingual education. The difference—between English-first and English-second—is crucial, and, in fact, once one learns English, one should move on to Spanish.

October 12th, 2006

A version of this blog post appeared as an action alert for the American Conservative Union.

Conservatives in Colorado haven’t had much to cheer about recently. Amendment 39 changes that prospect.

For too long, the only demand of education funding has been more money. Indeed, owing to Amendment 23, Colorado taxpayers have seen their public education costs rise to record levels every year.

Amendment 39 reverses this trend to “more education for more money” by implementing what columnist George Will calls the 65% solution. Simply put, this program will ensure that 65% of K-12 public school funding reaches Colorado’s classrooms, teachers and students, rather than lining the coffers of bloated bureaucracies.

Like all good legislation, Amendment 39 reprioritizes expenditures instead of raising taxes. Amendment 39 is also flexible, phased-in and allows a governor to grant a waiver if a school district has a legitimate reason why 65% cannot be reached, such as rural transportation costs.

While this reform should be implemented nationally, it’s particularly important in Colorado. For only 58 cents of every education dollar currently reaches the state’s classrooms, making them the 47th least-funded in the country.

No wonder fellow conservatives from around the country are promoting the 65% solution for their states. Texas Governor Rick Perry of Texas and Georgia Governor Sonny Perdue have implemented it, while gubernatorial candidates Dick Devos (MI), Ken Blackwell (OH), Mark Green (WI), Charlie Crist (FL) and your own Bob Beauprez have all endorsed it.

So do your part for Colorado taxpayers, parents and students. Make classroom instruction Colorado’s first priority in education by voting yes on Amendment 39 in November.

Learn more here.

April 4th, 2005

A version of this blog post was submitted as a nomination for the Hamilton College Christian A. Johnson Professorship.

Last summer, as I struggled to concretize a proposal for a Watson or Bristol postgraduate fellowship, I knew there was one person whose guidance I needed. I had talked with others, but no one had this person’s ability to explain any subject I’d ever asked about with such clarity, conciseness, context and cogence. Add this to patience that never flags and a wit that never runs dry, and this is why I think of Al Kelly as a personal encyclopedia.

I showed up unannounced at his office one weekday, doubtless while he was hard at work on his own research. What made our meeting special is Professor Kelly’s consistent brilliance to immediately distill the essence of an issue. Since my passion for a fellowship far outran any specific ideas for it, we spent about an hour and a half clarifying the reason for and goals of my project. Not where I would travel, or what I would do, or how I would do it, but simply why. Surely, anybody else would have either given up or moved on after say 20 minutes, but here was Professor Kelly calmly, happily connecting disparate dots, drawing out the big picture, and raising points as important as they were seemingly hidden. He knew that without a sound foundation, I was dooming myself to failure.

Yet rather than condescend whatsoever—how, with his intelligence, he does this is extraordinary—Professor Kelly never interrupted but let me hold forth as I attempted to verbalize my thoughts. Only when I finished, as is his unique habit, did he reply, speaking slowly and humbly, choosing his words thoughtfully, and asking me pointed questions. When I left, he transformed my mental chaos into lucidity.

* * *

When I returned to the Hill in the fall, having spent the summer interning at Time magazine, I decided to attend the first faculty meeting as a reporter for the Spectator. As one of maybe three separate students among maybe 150 professors, I entered the Events Barn with uncertainty. Then I spotted Al Kelly, holding court at the back of the room in his usual big chair. I breathed in relief, pulled up a seat and settled in. As the meeting proceeded, he explained some of the finer procedural points, and provided some funny human-interest anecdotes for my article. By next month’s meeting, it was as if I were a colleague.

In October the Spectator asked me to interview President Stewart about the coming presidential election. So I formulated a bunch of questions and then sought out Professor Kelly. I stopped by his office unannounced, and we spent 40 minutes ensuring that each question was relevant, distinct, compact and interesting. Forty minutes on what turned out to be 10 questions? Yes—and without checking his watch once. For unlike interviews I did for my column, this was my first interview to be printed as such, and since I’m an aspiring journalist, Professor Kelly knew it was crucial that I get it right.

Another indelible incident came a few months ago during the Susan Rosenberg affair. As I was weighing the competing arguments for Rosenberg’s appointment, I encountered Professor Kelly leaving the K-J building one night. I asked for his opinion, and in one crisp sentence he made explicit the fundamental principle at stake. I had had countless conversations about the controversy, but, again, Al Kelly was the only one who could simplify everything into a neat, small package.

He would engender another eureka moment for me during the Ward Churchill affair, but perhaps the most important one came during his European Intellectual History course, which I took as a junior. I had raised an objection to something he said, and in five words—“Watch your straw men, Jon”—he significantly altered my approach to scholarship. What this meant, he continued, was that although we all occasionally resort to weak or imaginary arguments, like straw, setup only to be summarily confuted, enlightened discourse proscribes such red herrings.

If this sounds simple, it is. Yet therein lies the beauty of this analysis, which, as is Professor Kelly’s wont, was at once readily comprehensible and crucially insightful. Indeed, his message embodied the goal of a liberal arts education: to further one’s knowledge not by expounding one’s own opinions but by understanding those of others. For this reason, I titled the column I would begin weeks later in the Spec, “No Straw Men.” Similarly, a few months later, I cited Professor Kelly’s exquisite monograph, Writing a Good History Paper, in an op-ed I wrote on journalism. He may be a historian by training, but his wisdom encompasses all disciplines.

* * *

Of course, all the above points to Al Kelly the mentor; doesn’t this guy—the Edgar B. Graves Professor of History after all—teach? Excellently. Al Kelly is of the old school of pedagogy, which means that he sees students not as incubators for his personal politics, but as diverse minds to be filled with classic knowledge. Accordingly, Professor Kelly is an eminently reasonable grader, who I would trust above all others to assess my work fairly. For rather than privilege one’s conclusion, he focuses on the way by which one reaches them. Consequently, his courses are rigorous (to set the tempo, he assigns homework not after but for the first class); challenging (a thorough grasp of the course material is never enough; students must make connections among and outside them); and thorough (you can’t cut any corners for an Al Kelly paper).

Indeed, class with Professor Kelly makes me believe that I’m getting my $35,000 worth of yearly tuition. I come away feeling enlivened and empowered, such that one day, following his Nazi Germany course, he and I continued a discussion from the library all the way to K-J—despite that I was going back to my dorm in North. Even when I didn’t do my homework, I always looked forward to each 75-minute session, because in simply listening to Professor Kelly lecture, I learned as much about that day’s topics as about life. Where else would I hear about the so-called four lies of modernity? (The check’s in the mail. I caught it from the toilet seat. I read Playboy for the articles. And it’s not about the money.)

Finally, rather than ask students just to defend or argue against a view, Professor Kelly requires that we engage it creatively. One typical question, from a final exam, went like this: pretend you’re Mary Wollstonecraft, and write a book review of Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France. Equally impressive is his feedback on our answers, which is why in January I asked him for feedback on my senior thesis in government. He uses few words, but they’re the pithiest I’ve ever received. Were he alive, William Strunk Jr., the initial author of The Elements of Style, would surely take great satisfaction in knowing that others take seriously his maxims to “omit needless words” and to “make every word tell.” The world could use more Al Kellys.

Unpublished Notes

I met Al Kelly in the fall of 2002, when I was a sophomore. We were serving ourselves from a buffet in the Philip Spencer House, following or before a lecture, and I wanted to strike up a conversation. So I asked him what he thought of David Horowitz’s performance in a recent panel with Maurice Isserman. I forget his answer, but when I replied that Horowitz complains he rarely gets invited to speak about the 60s, a subject on which he considers himself an authority, Al’s reply was, as usual, witty and indelible: “That’s because he’s a jerk.”

As a then-fan of Horowitz’s, I didn’t know what to say, and let the issue drop. Yet I couldn’t shake my discomfort, and when I later did a Google search, it was evident Al was right. With just five little words he had changed my mind on something about which I was convinced those with disagreed with me had to be biased.

My next encounter with Al came in my sophomore seminar, Classics of Modern Social Thought, which he teaches with Dan Chambliss. To be honest, I disliked the course, and even argued with the professors about a couple of grades. Neither budged, yet for some reason, as students were choosing our courses for the next semester, I signed up for Al’s European Intellectual History course.

Of course, when I returned to the Hill for my junior year, I had second thoughts about taking another course with Professor Kelly. Hadn’t I suffered through my sophomore seminar? Shouldn’t my grade have been higher? And who cared about European intellectual history anyway? Nonetheless, I decided to attend the first class, which turned out to be one of the best decisions I’ve made while here. Indeed, so much did I enjoy and benefit from learning under Al Kelly that next semester I took his Nazi Germany course, which proved to be my favorite.

* * *

Try as I do to stump him—averaging probably three questions a class—it seems his knowledge knows no bounds. Moreover, his ability to impart that expertise—whenever I ask, however confusedly I render my questions—never ceases to flow forth clearly, concisely, contextually and cogently.

* * *

He made a point to shake the hands of each student after the last class in his Nazi Germany course.

February 11th, 2005

A version of this blog post appeared in the Utica Observer-Dispatch on February 11, 2005, and was noted on Cox & Forkum on March 28, 2005.

HAMILTON COLLEGE, February 1, 2005— On Thursday, February 3, Ward Churchill, a Professor and Chair of Ethnic Studies at the University of Colorado at Boulder, will participate in a panel here titled “The Limits of Dissent.” That he will discuss his infamous essay, “Some People Push Back: On the Justice of Roosting Chickens”—wherein, among other bizarre indictments, he calls the civilians in the World Trade Center on 9/11 “little [Adolf] Eichmanns”—has rightly invited debate.

What troubles many the most is obviously Churchill’s ramblings on 9/11, which are odious, fatuous and sorely lack both credibility and seriousness. Indeed, in an interview in April 2004, he said it was a “no-brainer” that “more 9/11s are necessary.” Last week he declined to back off his Eichmann analogy, which evidently is one of his pet phrases. Then, in a statement on Monday, he assured us that the phrase applies “only to . . . “technicians.’”

With such apoplectic venom for America and Americans, one might think Mr. Churchill would just as fiercely champion the freedom of speech. In fact, for more than a dozen years, he has led organized protests, the last one culminating in arrest, to suppress Columbus Day parades. He reminds his followers that the First Amendment doesn’t protect outrageous forms of hate speech. Apparently, hypocrisy doesn’t bother those who thrive on it.

Yet controversy, especially in academe, is necessary, no idea is dangerous or too radical, and the best disinfectant is sunlight. The bigger issue is that it behooves institutions of higher education, particularly elite ones like Hamilton, to maintain high standards in proffering their scarce and prominent microphones. A commitment to free speech—even an absolute one—does not require a school to solicit jerks, rabble-rousers or buffoons.

This is not to say that the grievance or blowback explanation of 9/11—that it’s not who we are and what we stand for, but what we (U.S. foreign policy) does—doesn’t deserve attention. It does, as Newsweek’s Christopher Dickey argued here last semester. The point is, What suddenly makes Ward Churchill an authority on Islamic terrorism? Ditto for Churchill’s colleague, wife and fellow panelist, Natsu Taylor Saito, whose newfound expertise and lecture subject is the Patriot Act. The answer lies not in “what?” but in “whom?”

That “whom” is the Kirkland Project for the Study of Gender, Society and Culture, a faculty-led organization, well funded primarily by the dean’s office. In recent months, the K.P. has become a lightning rod for Hamilton. Its appointment of Susan Rosenberg, a terrorist turned teacher who four years ago was serving out a 58-year sentence in federal prison, brought to the Hill heretofore the most damaging publicity in its 200-year history. Granted, since controversy inheres in its role as an activist interest group, the K.P. has made waves since its founding in 1996. The evidence, however, increasingly indicates that the group courts controversy—and only one side of controversy—as an end in itself.

To be sure, Churchill was initially scheduled to lecture on Indian rights and prisons, and the change in topic and format occurred at the direction not of the K.P. but of the college president. But surely no one doubts that Churchill was invited largely because he is a leftist radical (it’s worth noting that he lacks a PhD). Similarly, the K.P. excludes topics or speakers who don’t pass that ideological litmus test.

Whether it’s an appropriate for such a group to exist on campus is, fortunately, no longer taboo, since Hamilton’s administration has appointed a faculty committee to review the “mission, programming, budget, and governance” of the Kirkland Project. Formally, the review is a routine procedure about every 10 years, but in this case it’s overdue. Whatever the ensuing recommendations, one hopes that the Board of Trustees and the Kirkland Endowment will also take this opportunity to reevaluate the use of their generosity. The college boasts too much talent to be consumed by another gratuitous scandal.

Addendum (5/7/2005): On September 11, 2002, the following words were written: “The real perpetrators [of the 9/11 attacks] are within the collapsed buildings.” The writer? Saddam Hussein. Would Ward Churchill have disagreed?

Addendum (7/9/2005): Proving that what you say is as important as how you say it, now even Fouad Ajami is on record that U.S. foreign policy—specifically, our “bargain with [Mideast] authoritarianism”—“begot us the terrors of 9/11.”

Of course, there’s no outcry over Ajami since, unlike Churchill, this professor does not need to use phrases like “little Eichmanns” to make his point.

January 27th, 2005

A version of this blog post appeared in FrontPage Magazine on January 27, 2005.

They call academe the ivory tower. But sometimes the ivory tower is not as aloof as it often seems. To the contrary, as the faculty of Hamilton College gathered for their last monthly meeting of 2004, they tackled the agenda with such pragmatism and sincerity one might have mistaken the scene for a town hall meeting.

Except the debate wasn’t about war or taxes or health care. And then there was the philosophy professor who invoked Kant. No, the 800 pound gorilla was Susan L. Rosenberg, Hamilton’s newest faculty member. As an “artist/activist in residence” under the aegis of the Kirkland Project for the Study of Gender, Society and Culture, Ms. Rosenberg was scheduled teach a five-week seminar this winter titled “Resistance Memoirs: Writing, Identity, and Change.”

Sound like a typical teacher? Think again. For only via an act of clemency, among 139 commutations and pardons President Clinton issued two hours before he left office in 2001, was Rosenberg freed from federal prison. Seventeen years earlier, she had been convicted of possessing false identification papers and a stockpile of illicit weapons, including over 600 pounds of explosives—approximately the same poundage Al Qaeda used to bomb the U.S.S. Cole in 2000. To be sure, the feds never charged Rosenberg with murder, but as National Review’s Jay Nordlinger wrote shortly after her commutation, she was a support player—“driver of getaway cars, hauler of weapons, securer of safe houses”—in the Weather Underground, the notorious American terrorist group active in the late 60s and 70s.

Rosenberg has steadfastly denied involvement in the Underground’s most infamous operation, the robbery of a Brink’s money truck in 1981 that left two people seriously wounded and three dead, including two police officers. Moreover, former New York City mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani, who as a U.S. Attorney prosecuted the case, eventually dropped her indictment. Does the presumption of innocence before proven guilty exclude Susan Rosenberg?

Critics contextualize the Brink’s trial, as they do Ms. Rosenberg’s. In the former, the absence (due to memory loss) of a key witness compelled the government to shelve the charges against Ms. Rosenberg without prejudice. In the latter, with the courthouse thick with guards and helicopters whirring overhead, security was costly. Protests and Ms. Rosenberg’s theatrics—she proclaimed herself a “revolutionary guerrilla,” harangued the court about world affairs, demanded, and received, the maximum sentence for her “political” activities—further exacerbated the milieu. The government finally decided to spare taxpayers the expense and time for what would likely be a concurrent verdict.

Furthermore, as Roger Kimball opined in the Wall Street Journal in December, “It is by no means clear that Susan Rosenberg is an ‘an exemplar of rehabilitation,’” as Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz, Professor of Comparative Literature and Director of the Kirkland Project, calls her. Instead, in an interview on Pacifica radio days after her release, Ms. Rosenberg parses her words to renounce individual but not collective violence. “Nobody renounces collective violence,” Professor Rabinowitz assured me. In this way, Ms. Rosenberg’s alleged rehabilitation pertains to means, not ends; she remains an unreconstructed extremist, who even as the Kirkland Project inadvertently admitted in a statement, “maintain[s] her ideals.”

Indeed, Ms. Rosenberg exploits the cachet of her past to advance her present. This is why she terms her course one of “resistance,” implying not change but calcification, and clings to her self-description as a onetime “political prisoner.” “The last time I checked,” however, says Brent Newbury, president of the Rockland Country Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, “we don’t have political prisoners in this country. We have criminals.”

At the same time, Susan Rosenberg is on record in her clemency appeal as accepting responsibility for her actions and for renouncing violence. Both Birch Bayh, a former U.S. senator who chaired the subcommittee on constitutional rights, and the chaplain at Rosenberg’s penitentiary in Danbury, CT, under whose supervision she worked for three years, have vouched for her sincerity. And in any event, don’t actions speak louder than words? Ms. Rosenberg has a master’s degree in writing, has won four awards from PEN Prison Writing programs, and for the past several years has taught literature as an adjunct instructor at CUNY’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice. She also has lectured at such institutions as Columbia, Brown and Yale. Such progress was hard-earned and is hard evidence.

However, some believe that certain acts are so heinous, they disqualify one for full-fledged rehabilitation. Time never exonerates serious criminality. As U.S. Attorney Mary Jo White wrote to the U.S. Parole Commission, “Even if Susan Rosenberg now professes a change of heart . . . the wreckage she has left in her wake is too enormous to overlook.” Economics professor James Bradfield concurs: “[H]er character, as manifestly demonstrated by the choices that she made as an adult over a sustained periods of years, would preclude her appointment to the faculty of Hamilton College.”

President Joan Hinde Stewart disagrees. “No one is irredeemable—I think that is incontrovertible,” she told the faculty. Learning from mistakes “affirms the value of education,” adds Professor Rabinowitz. Most people who have seen The Shawshank Redemption, or listened to a recovering alcoholic speak about his disease, would agree. For while some may not deserve a third or fourth chance, most should get a second. People can and do change, and when we stop believing in that capacity to grow, in the transformative power of the human spirit, we stop believing in the reason to get up in the morning.

But it behooves us to distinguish between morbid curiosity and value. Certainly, Ms. Rosenberg offers a unique perspective, but neither uniqueness nor exclusivity is an end in itself. The end is academic substance. And the means is academic credentials, since even if “Resistance Memoirs” is merely a five-week, half-credit course, that credit nonetheless counts toward a Hamilton College diploma. To be sure, adjuncts need not have a PhD or scholarly publications; yet it is not too much to ask, as several professors did fruitlessly, that Ms. Rosenberg’s curriculum vitae be made available. Plus, just as John Kerry made his service in Vietnam a cornerstone of his recent presidential bid, and consequently suffered criticism for that admittedly heroic record, so the Kirkland Project’s distortion of Ms. Rosenberg’s background invited scrutiny. “[I]ncarcerated for years as a result of her political activities with the Black Liberation Army,” as fliers around the campus announced, sanitizes a vile and vicious rap sheet.

Moreover, surely there was someone with more qualifications, or at least with less baggage? In fact, Professor Rabinowitz told me, “We did not look for anyone else.” In other words: we wanted Susan Rosenberg because she was a convicted, leftwing terrorist.

Rosenberg’s supporters, who include Professors of History, Government and Comparative Literature Maurice Isserman, Stephen Orvis and Peter Rabinowitz (Nancy’s husband), believe the controversy resulted from right-wing polemicists into whose preexisting agendas Susan Rosenberg happened to fall. After all, the Kirkland Project, many of whose almost 40 members are Hamilton professors, approved Ms. Rosenberg’s hire, and Ms. Rosenberg visited Hamilton in February, during which she participated in two panels on “the science of incarceration” and “making change/making art.” Her presence, then or at the aforesaid schools, stirred little attention (though John Jay has since announced that it will not renew her contract.)

All this is true, yet all this discounts the qualitative difference between teaching a credit-bearing course for five weeks and lecturing for two days. Such naïveté further snubs the hundreds of heartfelt pleas to the college, not only from readers of FrontPage Magazine but also from people whom the Weather Underground’s activities intimately, permanently affected. Edward F. Moore, President of the New York state chapter of the F.B.I. National Academy Associates, who wrote an open letter to President Stewart, has no axe to grind, merely a conscience to quiver.

In the end, Susan Rosenberg withdrew herself. Her legacy at Hamilton will not be the pros and cons of her appointment, but the process by which the arguments and their proponents wrestled: passionately but professionally, with moral seriousness and deep principles on both sides. The Board of Trustees wisely refrained from micromanaging this explosive affair, trusting instead in free and open exchange among the faculty. They, like students and alumni, did not disappoint. In fact, our letters and essays in the school newspaper and discussions in class, on ListServs and at meetings, testify to the continuing vitality and vigor of higher education.

February 1st, 2003

A version of this blog post appeared in the Hamilton College Spectator (February 2003) and Capitalism Magazine (March 31, 2003).

Last semester Raja Halwani gave a lecture at Hamilton on what he called “the just solution” to the Israeli-Palestinian crisis. Last week Daniel Pipes did the same. For those unfamiliar with the former, consider Mr. Halwani’s comparison with others in that lecture series. Ben Barber, author of Jihad vs. McWorld, a text many Hamilton professors use in their courses, spoke on globalization. George Borjas, director of a program on urban poverty at Harvard, spoke on today’s urban neighborhoods. Doug Massey, among America’s leading demographers of immigration, spoke on immigration. Victor Hanson, author of Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power, spoke on the relationship of past wars to the current war.

And then we had Raja Halwani, who, according to the blurb for his talk, “has published numerous articles” about “aesthetics, ethics, and the philosophy of sex and love.” The connection to Israel? Mr. Halwani, the professor who announced his visit informed me, “is a scholar who has written on issues in ethical theory and political theory which have been published in peer-reviewed journals.”

But does a PhD and publication in peer-reviewed journals on ethics and politics qualify someone to speak expertly on Israeli-Palestinian affairs? If so, then the Mideast punditocracy just grew exponentially. Surely, to speak under the aegis of Hamilton’s Arthur Levitt Public Affairs Center and the philosophy department, both of whom sponsored Mr. Halwani’s talk, requires higher standards than this. In short, speakers should speak on the subject of their expertise.

Yet the further I researched Mr. Halwani’s credentials, the clearer it became that he lacked them. It seems instead that a personal friendship occasioned his visit. Indeed, in the Q&A after his speech, Mr. Halwani thanked—not the Levitt Center or the philosophy department—but the aforesaid professor.

On a related matter, consider these words from an op-ed Mr. Halwani penned in October 2001. “Anyone . . . familiar with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict must know the kind of oppression that the Palestinians have to endure under Israeli rule. The U.S. has supported Israeli hegemony over Palestinian lives without so much as lifting an eyebrow.”

While Mr. Halwani is entitled to his opinion in the first sentence, facts make his second sentence false. To give just one example, he simply ignores the existence, since 1949, of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), an organization whose most generous sponsor—contributing more than a quarter of its $400 million 2002 budget—is the United States.

His lecture evinced further overt selectivity. It also reeked of superciliousness, as when Mr. Halwani told a student, in response to a question regarding the size of Israel vis-à-vis its neighbors, “Well, I’ll communicate your wishes to the Palestinians, and get back to you.”

By striking contrast, Daniel Pipes is director of the Middle East Forum, a think tank, has lectured in 25 countries, and his work has been translated into 18 languages. He has published considerably in peer-reviewed journals, and authored 12 books on the Middle East and Islam. The Wall Street Journal calls him “an authoritative commentator on the Middle East.”

I began my introduction for Dr. Pipes by noting, “Regularly, speakers lecture at Hamilton College. Rarely, however, do they bring to the Hill a viewpoint that is a breath of fresh air—especially on an issue that many intellectuals have made noxious.” As it happened, my words had an even larger meaning than I originally foresaw. The night before Pipes’s visit, Professor of Anthropology Douglas Raybeck had sent an all-campus e-mail attributing a racist motive to Mr. Pipes. Wrote Raybeck: “Mr. Pipes became the bête noire of U.S. Muslim organizations after writing an article for the National Review in 1990 that referred to ‘massive immigration of brown-skinned peoples cooking strange foods and not exactly maintaining Germanic standards of hygiene.’”

Alas, Professor Raybeck, a man of generally impeccable scholarship, though he mentioned Pipes’s Web site, omitted the context for this quote. In fairness, I circulated Pipes’s response via another all-campus e-mail: “My article points to two Western fears of Islam, one having to do with jihad, the other having to do with immigration. I dismiss the former, then move on the latter, which I then characterize in the words [Raybeck] quotes. This is my description of European attitudes, not of my own views” (my emphasis).

Thankfully, Associate Professor of Art Steve Goldberg also replied to the campus—with disheartening accuracy: “It never ceases to amaze me who on this campus ‘pipes up’ to caution us as to the possible biases of visiting speakers. Notice that when it is a left-of-center speaker, he is considered to be neutral and unbiased, thus requiring no ‘sagely’ cautionary advice. However, stray ever so slightly to the right and our so-called liberal instructors feel it their duty to protect us from thinking for ourselves.” Indeed, it’s a sad day when people, above all educators, allow their political ideologies rather than the facts, as they clearly exist, to guide them.

Scholars “use an intellectual scalpel…