To Torture or Not to Torture

A version of this blog post appeared in the Hamilton College Spectator on April 30, 2004.

We know the general location, we know it will happen in the next 24 hours, and we’re confident the person we’ve nabbed knows what, where and when.[1] The question before us: to torture or not to torture?

Although we’ve now heard Attorney General-nominee Alberto Gonzales condemn the practice, seen Specialist Charles Granger sentenced to 10 years for committing it, and read half a dozen new books highlighting the route from Gonzales’ keyboard to Granger’s fists, it seems we are no closer to an answer. We urgently need one, but the very subject makes us wince and demur, insulated by the cliché, “Out of sight, out of mind.” Of course, this only perpetuates the problem, for without the check of a national debate, government defaults to its worst instincts. Here, then, is a modest start in addressing today’s moral imperative.

We should first remember that this hypothetical represents an emergency, and since emergencies distort context, they make it tortuous to retain a fully rational resolution. Similarly, emergencies are emergencies—people do not live in lifeboats—so such context should not form the basis for formulating official policy

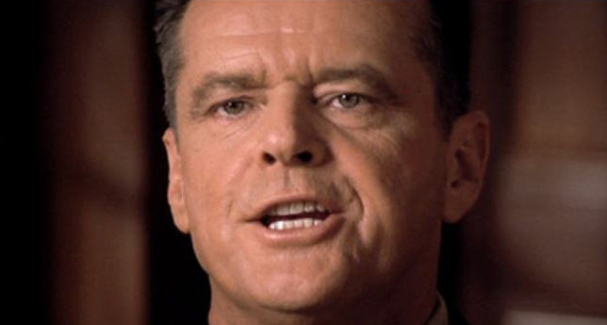

Nonetheless, torture advocates argue that the end justifies the means, which amounts to an often obvious but equally precarious utilitarian calculus: had we, say, captured a 20th 9/11 hijacker on 9/10, many would have doubtless approved his torture to elicit information. Advocates also argue that once we determine a suspect knows something, he thereby becomes a threat and forfeits his rights. Playing Colonel Nathan R. Jessup in A Few Good Men (1992), Jack Nicholson memorably crystallized the point: “[W]e live in a world that has walls, and those walls need to be guarded by men with guns. Who’s gonna do it? You?. . . . [D]eep down in places you don’t talk about at parties, you want me on that wall. You need me on that wall.” Thus, torture is a “necessary evil,”[2] made particularly imperative by a post-9/11—and now post-3/11 (Madrid)—world.

Of course, governments have always used the excuse of an emergency to broaden their powers. Referring to the French Revolution, Robespierre declared that one cannot “expect to make an omelet without breaking eggs.” The Soviets alleged that their purges were “temporary.” The Nazis said extraordinary times necessitated extraordinary measures. And, in the same way, 45 days after 9/11, in government’s characteristic distortion of words, Congress adopted the so-called Patriot Act (which in the heat of the moment many of the lawmakers voting for it did not even read, in whole or in part). Then, 13 months later, the Bush administration floated a second Patriot Act. Such is the pattern of and path toward despotism.

And yet, the renowned civil libertarian, Alan Dershowitz, is perhaps torture’s most famous advocate. Dershowitz favors restricting the practice to “imminent” and “large-scale” circumstances. But, again, by such seemingly small steps we creep further toward the Rubicon: since we have already surrendered such power, a precedent has been established, and the rest is only a matter of details and time.

Indeed, once we legitimate torture to save New York City, it becomes much easier to legitimate its use to save “just” Manhattan. And then “just” Times Square. And then “just” the World Trade Center. Before we let a judge issue what Deroshowitz terms “torture warrants” on a case-by-case basis, we need to define our criteria precisely. Are they to save a million people? A thousand? A hundred? The President? Members of the Cabinet? Senators? Only in cases involving a “weapon of mass destruction”?

Similarly, if torture makes terrorists sing, as it often does in foreign countries, why shouldn’t we use it against potential terrorists? And then to break child pornography rings and to catch rapists? And then against drug dealers and prostitutes? After reading of endless abuses by government officials using forfeiture, I.R.S. audits, graft, payoffs, kickbacks and the like, it is naïve to think that once we collectively sanction torture, that torture would somehow be exempt from the temptress of absolute power. Do not say it cannot happen in America. It already has.

Footnotes

[1] This is the “ticking-bomb” hypothetical, which Michael Walzer described in “Political Action: The Problem of Dirty Hands,” Philosophy and Public Affairs 2, 1973, 166–67, and Alan Dershowitz popularized in Why Terrorism Works: Understanding the Threat, Responding to the Challenge (2002). But as Arthur Silber of the LightofReason blog notes, we should modify this Hollywood fantasy. For instance, has the suspect confessed to knowledge and refuses to spill it, or does he profess not to know anything when we believe he does?

[2] The term “necessary evil” is contradictory. Explains psychotherapist Michael Hurd: “[T]here are no necessary evils. If something is truly evil, there’s no way it can be necessary, and if it is truly necessary to the well-being of a rational man’s life, it’s not evil, but good.”

Unpublished Notes

The conservative analyst Andrew Sullivan adds, “In practice, of course, the likelihood of such a scenario is extraordinarily remote. Uncovering a terrorist plot is hard enough; capturing a conspirator involved in that plot is even harder; and realizing in advance that the person knows the whereabouts of the bomb is nearly impossible.”

“What the hundreds of abuse and torture incidents have shown is that, once you permit torture for someone somewhere, it has a habit of spreading. Remember that torture was originally sanctioned in administration memos only for use against illegal combatants in rare cases. Within months of that decision, abuse and torture had become endemic throughout Iraq, a theater of war in which, even Bush officials agree, the Geneva Conventions apply. The extremely coercive interrogation tactics used at Guantánamo Bay ‘migrated’ to Abu Ghraib. In fact, General Geoffrey Miller was sent to Abu Ghraib specifically to replicate Guantánamo’s techniques. . . .

“[W]hat was originally supposed to be safe, sanctioned, and rare became endemic, disorganized, and brutal. The lesson is that it is impossible to quarantine torture in a hermetic box; it will inevitably contaminate the military as a whole. . . . And Abu Ghraib produced a tiny fraction of the number of abuse, torture, and murder cases that have been subsequently revealed. . . .

“What our practical endorsement of torture has done is to remove that clear boundary between the Islamists and the West and make the two equivalent in the Muslim mind. Saddam Hussein used Abu Ghraib to torture innocents; so did the Americans. Yes, what Saddam did was exponentially worse. But, in doing what we did, we blurred the critical, bright line between the Arab past and what we are proposing as the Arab future. We gave Al Qaeda an enormous propaganda coup, as we have done with Guantánamo and Bagram, the ‘Salt Pit’ torture chambers in Afghanistan, and the secret torture sites in Eastern Europe. In World War II, American soldiers were often tortured by the Japanese when captured. But FDR refused to reciprocate. Why? Because he knew that the goal of the war was not just Japan’s defeat but Japan’s transformation into a democracy. He knew that, if the beacon of democracy—the United States of America—had succumbed to the hallmark of totalitarianism, then the chance for democratization would be deeply compromised in the wake of victory. . . .

“What minuscule intelligence we might have plausibly gained from torturing and abusing detainees is vastly outweighed by the intelligence we have forfeited by alienating many otherwise sympathetic Iraqis and Afghans, by deepening the divide between the democracies, and by sullying the West’s reputation in the Middle East. Ask yourself: Why does Al Qaeda tell its detainees to claim torture regardless of what happens to them in U.S. custody? Because Al Qaeda knows that one of America’s greatest weapons in this war is its reputation as a repository of freedom and decency. Our policy of permissible torture has handed Al Qaeda this weapon—to use against us. It is not just a moral tragedy. It is a pragmatic disaster.[1]

Finally, we must decide whether our government should conceal or inform us of its torture policies. Whether one opposes torture, I agree with Deroshowitz that “[d]emocracy requires accountability and transparency”;[2] “painful truth,” as Michael Ignatieff, author of The Lesser Evil (2004), puts it, “is far better than lies and illusions.”[3] As such, the U.S. government should clarify what tactics it is using and which are still off limits, so the American people can vote our views, via our representatives, into action.

“It is an axiom of governance that power, once acquired, is seldom freely relinquished.”[4]

“Another objection is that the torturers very swiftly become a law unto themselves, a ghoulish class with a private system. It takes no time at all for them to spread their poison and to implicate others in what they have done, if only by cover-up. And the next thing you know is that torture victims have to be secretly murdered so that the news doesn’t leak. One might also mention that what has been done is not forgiven, or forgotten, for generations.”[5]

“The chief ethical challenge of a war on terror is relatively simple—to discharge duties to those who have violated their duties to us. Even terrorists, unfortunately, have human rights. We have to respect these because we are fighting a war whose essential prize is preserving the identity of democratic society and preventing it from becoming what terrorists believe it to be. Terrorists seek to provoke us into stripping off the mask of law in order to reveal the black heart of coercion that they believe lurks behind our promises of freedom. We have to show ourselves and the populations whose loyalties we seek that the rule of law is not a mask or an illusion. It is our true nature.”[6]

Even if an exception is justified, further exceptions, likely to be increasingly unjustified, will likely ensure.

[1] Andrew Sullivan, “The Abolition of Torture,” New Republic, December 19, 2005.

[2] Alan Dershowitz, “Is There a Torturous Road to Justice?,” Los Angeles Times, November 8, 2001.

[3] Michael Ignatieff, “Lesser Evils,” New York Times Magazine, May 2, 2004.

[4] Mark Danner, [Untitled], New Yorker, July 29, 1991.

[5] Christopher Hitchens, “Prison Mutiny,” Slate, May 4, 2004.

[6] Michael Ignatieff, “Lesser Evils,” New York Times Magazine, May 2, 2004.

Comments

Comments