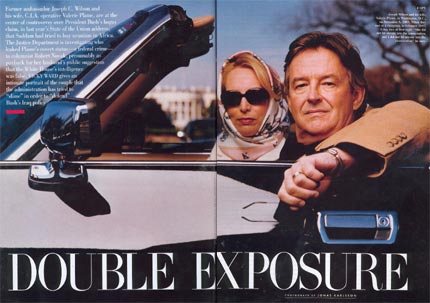

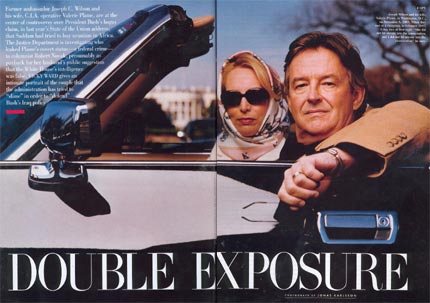

Search results for the tag, "Valerie Plame Affair"

October 2nd, 2005

In January 2004, Scooter Libby signed a waiver allowing Judy Miller to testify about their confidential conversations regarding Valerie Plame Wilson. But as Miller’s former lawyer Floyd Abrams later said, that waiver was “required as a condition for Mr. Libby’s continued em-ployment at the White House.” Hence, most journalists agreed that the waiver was, as Abrams put it, “inherently ‘mixed,’” or coercive.

This left Miller with two options. After publicly announcing that she viewed the waiver as insufficient, she could wait for Libby to assure her, specifically and directly, that he had voluntarily abrogated their agreement. Alternatively, she could ask him herself.

Matt Cooper took the latter route. After receiving—an hour before he would have been incarcerated—“an express personal release from my source,” who turned out to be Karl Rove, he agreed to testify and went free. Miller chose the former route, and so went to jail.

According to Abrams, Libby’s failure to contact Miller as the case proceeded led her to conclude that he did not want her to testify.

This is understandable. If a subpoena requires a reporter to break her confidentiality with a source, then, assuming the source knows about the subpoena (which, in this case, anyone read-ing a newspaper did), the source should approach the reporter, not vice-versa.

But I fail to see the great danger if the reporter approaches the source, as Cooper did (through his lawyer). Especially if the consequence of not doing so is four months in jail—and possibly more—a phone call or an e-mail asking for clarification seems eminently fair.

It’s therefore difficult not to conclude that Judy Miller’s 85 days in jail resulted not from the special prosecutor’s obstinacy, but from her own.

Addendum (10/2/2005): The New York Times: “[P]eople involved in the case have said Ms. Miller did not understand that the waiver had been freely given and did not accept it until she had heard from Mr. Libby directly.”

Arianna: “The claim that Miller ‘has finally received a direct and uncoerced waiver’ is laughable… and, indeed, has already been laughed at by (1) my increasingly frustrated sources within the Times (2) a chorus of voices in the blogosphere (see here, here, and here) and (3) (and much more significantly) Joseph Tate, Scooter Libby’s lawyer, who told the Washington Post yesterday that he informed Miller’s attorney, Floyd Abrams, a year ago that Libby’s waiver ‘was voluntary and that Miller was free to testify’ [actually, these are not Abrams’s words but the Post’s summary].

“So it defies credulity for Miller, Sulzberger [the Times’s publisher], and Bill Keller [the Times’s editor] to keep insisting that Libby’s earlier waiver was coerced when Libby says that it wasn’t. I don’t have much good to say about the vice president’s chief of staff, but I don’t doubt that he knows the difference between being coerced and acting on his own free will.

The Washington Post: “[Tate] said last night [Sept. 29] that he was contacted by [Robert] Bennett [Abrams’s replacement] several weeks ago, and was surprised to learn that Miller had not accepted [Libby’s year-old waiver] as authorization to speak with prosecutors.

“‘We told her lawyers it was not coerced,’ Tate said. ‘We are surprised to learn we had anything to do with her incarceration’ [emphasis added]. . . .

“In July, when Chief U.S. District Judge Thomas F. Hogan ordered Miller to jail, he . . . stress[ed] that the government source she ‘alleges she is protecting’ had released her from her promise of confidentiality.

Addendum (10/4/2005): Miller tells her paper, “I had been in jail, and I thought maybe Scooter Libby was thinking about that and that he might be prepared to do something that, for whatever reason, he didn’t feel comfortable doing before.”

Also from today’s Times: Miller had two other reasons for holding out:

1. She wanted a pledge from Fitzgerald that her testimony would be limited to her conversations with Libby and would not address other sources.

2. She wanted to redact her notes herself, rather than having to submit them to a third party, before turning them over to Fitzgerald.

July 17th, 2005

1. Doug Clifton, editor of the Cleveland Plain Dealer:

[T]wo stories of profound importance languish in our hands. The public would be well served to know them, but both are based on documents leaked to us by people who would face deep trouble for having leaked them. Publishing the stories would almost certainly lead to a leak investigation and the ultimate choice: talk or go to jail.

Because talking isn’t an option and jail is too high a price to pay, these two stories will go untold for now.

Read more from Editor and Publisher and the New York Times.

2. The Washington Post:

Time reporters have said that at least two sources have told them they would no longer provide information because the company turned over [Cooper’s] documents.

Addendum (7/23/2005): Pearlstine confirms, to the Senate Judiciary Committee, that Time reporters have received e-mails from sources saying they no longer trust the magazine.

Addendum (10/1/2005): Jim Kelly, Time’s managing editor, tells the New York Times, “Looking at what we’ve managed to publish since [Cooper testified], it is very hard for me to point to any damage that was done to Time magazine with its sources.”

July 15th, 2005

On July 6, having received an hour earlier, “in somewhat dramatic fashion . . . an express personal release from my source,” Matt Cooper agreed to testify. But as the New York Times reports, that source—Karl Rove—never gave Cooper the release himself. Rather, the release resulted from a “frenzied series of phone calls initiated that morning” by Cooper’s lawyer, Richard Sauber, to Karl Rove’s lawyer, Robert Luskin, and which involved the special prosecutor.

Here’s what happened (with additional reporting from Editor and Publisher). On his way back from Alaska to Washington on the night of July 5, Sauber passed through Chicago at 6 a.m., where he picked up the Times and the Wall Street Journal. Back on the phone, he read an article in the Journal that quoted Luskin as saying, “Mr. Rove hasn’t asked any reporter to treat him as a confidential source in the matter. So if Matt Cooper is going to jail to protect a source, it’s not Karl he’s protecting.”

Sauber immediately called Cooper from the plane, and they agreed to ask Luskin for a specific release from Rove. “I think we should take a shot,” Cooper recalled. “I said, ‘Yes, it’s an invitation.’”

When he landed in Washington, Sauber called Luskin, who called back at around 12:30 p.m.—an hour and half before court re-adjourned. Luskin dictated a waiver to Sauber, who then sent it Luskin, who signed and returned it at around 1 p.m.

The new waiver said only that Rove “affirm[ed]” his previous, blanket waiver, but it specified “any conversation he [Rove] may have had with Matthew Cooper of Time magazine during the month of July 2003.”

July 14th, 2005

Was Plame, in fact, undercover when she was outed?

Novak says the C.I.A. told him “the exposure of her name might cause ‘difficulties’ if she travels abroad,” but that “[i]t was well-known around Washington that Wilson’s wife worked for the C.I.A. . . . Her name, Valerie Plame, was no secret either, appearing in Wilson’s Who Who’s in America entry.”

Hitchens sneers that she “shuttle[d] dangerously ‘undercover’ between Georgetown and Virginia.”

Clifford May lets slip that he knew her name and identity before Novak’s column outing her: “I learned it from someone who formerly worked in the government and he mentioned it in an offhand manner, leading me to infer it was something that insiders were well aware of.”

On the other hand, Tim Noah uses a “simple test: did her friends and neighbors know she worked for the C.I.A.? They did not. Ergo, she was undercover.”

Addendum (7/17/2005): Joe Wilson admits, “My wife was not a clandestine officer the day that Bob Novak blew her identity.”

Addendum (7/21/2005): Yet it’s not that cut and dry, as Time magazine reports in two articles this week:

[A]s recently as the late 1990s she was working as a nonofficial cover (NOC) officer, one of a select group of operatives within the CIA who are placed in neutral-seeming environments abroad and collect secrets, knowing that the U.S. government will disavow any connection with them should they be caught. NOC officers cost millions of dollars to train and support. As a result of the leak, Plame is no longer able to work undercover.

[W]hile she may no longer have been a clandestine operative [at the time of the leak], she was still under protected status. . . . In the wake of the disclosure, foreign intelligence services were known to have retraced her steps and contacts to discover more about how the CIA operates in their countries.

Addendum (7/24/2005): Or is it, as the New York Times reports?

[Some] former C.I.A. officers say that by 2003 Ms. Wilson’s cover was already thin. Any serious inquiry would have revealed that Brewster Jennings [& Associates, the Boston shell company the C.I.A. set up] was little more than a mailbox. . . . Ms. Wilson . . . had been working for some time at agency headquarters in Langley, Va. And her marriage to a senior American diplomat, Mr. Wilson, ended any pretense of having no government ties.”At that point, she looks, walks and quacks like an overt agency employee,” said Fred Rustmann, a C.I.A. officer from 1966 to 1990, who supervised Ms. Wilson early in her career and calls her “one of the best, an excellent officer.”

Addendum (7/28/2005): Slate explains the different levels of cover in the C.I.A.

July 7th, 2005

The Los Angeles Times compiles a helpful Q&A (as does the Washington Post). From the Times:

Q: Administration officials signed agreements saying that reporters were free to reveal their identities. Despite that, why won’t reporters name their sources?

A: Miller, Cooper, and other reporters say such “blanket waivers” are not truly voluntary. Officials may have signed them fearing that, if they didn’t, they could be punished or fall under suspicion. Cooper and other journalists said they would talk about their sources only after being convinced that the officials’ willingness to be identified was voluntary, not coerced.

Addendum (7/9/2005): In Matt Cooper’s words:

I am with Judy that these government-issued waivers that the prosecutor has been handing out are not worth the paper they’re written on. . . . It’s coercive. It cannot be considered voluntary.

For C00per, a voluntary waiver must be “specific, personal and unambiguous.”

Addendum (7/15/2005): Floyd Abrams describes the government-issued waivers as “preprinted forms from the Department of Justice that people were instructed to sign by their superiors.”

Another question arises: If Fitzgerald knows who the government officials are, why does he need to question Miller and Cooper?

Answer: To corroborate information he has gathered during his investigation. As a general rule, prosecutors say they would never rely solely on notes taken by someone without also interviewing the note-taker.

July 6th, 2005

1. Judy Miller’s going to jail while Matt Cooper will testify.

2. Cooper and Miller now face four instead the original 18 months of jail, since (1) civil contempt is meant to be coercive rather than punitive, and (2) only four months remain in the term of the current grand jury investigating the case.

3. The real SOB is the leaker or leakers. “Last night I hugged my son goodbye and told him it might be a long time before I see him again,” Cooper told the court. Fortunately, just before today’s hearing, he received, “in somewhat dramatic fashion,” a direct personal communication from his source freeing Cooper from his commitment to keep the source’s identity secret.

July 3rd, 2005

1. According to Newsweek, which quotes Rove’s lawyer, Rove signed a waiver authorizing reporters to testify about their conversations with him. Yet Cooper, who interviewed Rove for the article he coauthored, has refused to discuss his sources save for Libby, who previously waived his confidentiality agreement. Why won’t Cooper tell Fitzgerald what Rove told him?

2. Where are Joseph Wilson and his wife Valerie Plame in all this? Why hasn’t someone asked for their comments?

3. Time Inc. considers its employees’ reportorial notes company property. What’s the Times’s policy?

Addendum (7/5/2005): Scott Shane follows-up on question two with a 1,900-word article in today’s Times.

Addendum (7/6/2005): Tim Noah replies to Shane. Noah also compiles a hyperlinked timeline of Plame’s public appearances and quotes.

Addendum (7/8/2005): Slate’s Explainer columns answers question three:

Who owns a reporter’s notes? It’s a murky issue, and one that hasn’t been fully resolved in court. According to the work-for-hire doctrine prescribed by the federal copyright statute, the employer who paid for the production of a work is considered its owner. In general, any notes, tools, or other materials that were created in the process of producing that work also belong to the employer. Rules for freelancers are somewhat less clear and depend on the exact terms of the contract. Some freelance contracts state explicitly that an article is being produced as a “work for hire.”

Despite the rules laid out by the federal copyright statute, many individual newspapers have their own policies on reporters’ notes. The Wall Street Journal’s parent company declares that “any and all information and other material” obtained by its employees on the job is its exclusive property. A New York Times spokesman says reporters’ notes are their own, by long-standing convention.

July 2nd, 2005

1. Fitzgerald subpoenaed Cooper on the basis on an article he coauthored for Time.com. How does Fitzgerald know that the “government officials” the article refers to spoke with Cooper and not Massimo Calabresi or John Dickerson?

2. How does Fitzgerald know that someone in the know spoke with Judy Miller, who merely conducted interviews on the matter but did not publish an article?

Addendum (7/9/2005): The New York Times answers question two: Fitzgerald has relied on secret evidence in persuading courts to order Miller jailed. He could have learned about her involvement through phone records and by questioning government officials.

Addendum (7/14/2005): Jack Shafer argues that “Fitzgerald seems bent on penalizing Miller for her knowledge of the case rather than for her proximity to the purported crime.”

Additional questions:

3. Why does Time but not the Times face contempt charges?

4. Is Karl Rove Cooper’s deep throat?

Addendum (11/21/2005): Time answers question three: “Miller . . . was originally subpoenaed along with the Times. After the newspaper said it had no relevant documents to hand over and that Miller’s notes—and the decision whether to turn them over—belonged to her alone, the court pursued only the subpoena against Miller. . . . In the Cooper case, the prosecutor went after e-mails and other information stored on computers owned by Cooper’s employer, Time Inc., which was subpoenaed and held in contempt when it refused to turn over the documents.”

Scholars “use an intellectual scalpel…